By Scott Ross

Home-viewing from The Armchair Theatre over the last three months; because there isn’t a single bloody thing in the cinemas worth the time, petrol, cash or personal energy it would take to go out. Although I will admit I was convinced by a friend to attend a special screening of Daughters of the Dust… thereby proving the point.

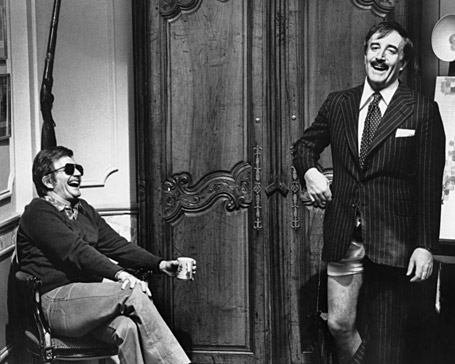

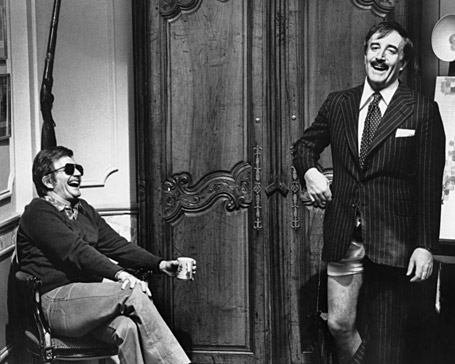

Tootsie (1982) Take one vanity project for a notoriously self-involved actor (Murray Schisgal writing a screenplay about acting for Dustin Hoffman); mix with a separate script by Don McGuire concerning an out-of-work performer donning drag for a soap-opera role that borrows a bit too liberally from Some Like it Hot, even unto its blond object of affection and unwanted middle-aged suitors; add in re-writes by a small army of scenarists headed by the great Larry Gelbart and including, un-credited, Barry Levinson, Robert Garland and Elaine May; bake by a director widely known as one of Hollywood’s most notorious writer fuckers (Gelbart claimed the movie was stitched together from any number of scenarists’ drafts), and the result should have been a disaster. Instead, through some weird alchemy it not only wasn’t but somehow those ingredients contrived to blend so well the picture became a small classic of its kind. Revisiting Tootsie from a 35-year remove, it seems almost miraculous: A popular comedy that tickles the mind as often as it does the ribs. And the direction, by Sydney Pollack, never a favorite filmmaker of this writer, looks as good now as it did in 1982; whatever its internal flaws (including a series of consecutive events supposedly encompassing a single evening that Gelbart later wrote was “a night that would have to last a hundred hours”) the picture is strikingly lovely, with Owen Roizman’s sumptuous lighting and the crisp, witty editing by Fredric Steinkamp and William Steinkamp giving it a patina of warmth and sophistication, a rare combination for any movie comedy.

Hoffman’s “Dorothy Michaels” ranks as one of the great comic creations in American movies, yet the actor also locates the loneliness of the character — or, rather characters, since everything Dorothy says and does is filtered through Michael Dorsey’s brain and emotions — and an essential sweetness and decency Michael himself lacks when he’s wearing pants.* As the unwitting object of Michael’s interests, Jessica Lange was a revelation in 1982, lightness and gravity in balance, and what she does is still astonishing in the sheer rightness of her every glance, inflection and wistful hesitation. Terri Garr is no less entrancing, in what is surely her best screen performance, and Bill Murray gets the picture’s best lines as Michael’s playwright roommate. (May created the character, and wrote his speeches.) Against his own wishes, Pollack took on the role of Hoffman’s agent, and their scenes together, reflecting some of the very real anger and frustration each felt toward the other, are among the movie’s comic highlights. The wonderful supporting cast includes Dabney Coleman as the sexist television director, Charles Durning and George Gaynes in the Joe E. Brown role(s), Doris Belack as the savvy “daytime drama” producer, Geena Davis as a nurse in the soap-within-a-film’s fictional hospital, and the late Lynne Thigpen as the show’s floor manager. Dave Grusin, who often floundered when composing for dramatic pictures, wrote for Tootsie one of his most felicitous comedy scores. It isn’t funny in itself, nor does it try to be; its alternate airs of peppy urbanity and plangent emotionalism make for a perfect juxtaposition that reflects the plot’s development and moods without attempting either to compete with them, or to ape the action.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

* Hoffman based Dorothy’s soft Southern vocal mannerisms on those of his friend Polly Holiday.

George C. Scott and Joanne Woodward in the movie’s radiant, moving final moments.

They Might Be Giants (1971) James Goldman has long been one of my favorite writers. While nowhere near as prolific (nor as well known) as his brother William, his smaller output includes the 1965 play and subsequent movie 1968 The Lion in Winter (for which he won an Academy Award); the beautifully compressed book for the landmark Stephen Sondheim/Harold Prince Follies, arguably the single greatest theatrical musical of the 20th century; the wonderfully conceived and unexpectedly moving Robin and Marian (1976); a superb novel about King John, Myself as Witness, in which Goldman re-examined an historical figure he felt he had maligned in his previous writing; and the play on which this lovely picture was based and for which he wrote the perfectly structured adaptation. Hal Prince produced the play’s only major production in London, later castigating himself for hiring the wrong director (Joan Littlewood) for the piece, although Goldman himself said he was unhappy with the script, which he subsequently withdrew from further production. The movie, while disappointing financially — presumably those involved expected another Lion in Winter — is a blissful variation on Arthur Conan Doyle, in which a mad retired jurist (George C. Scott) called Justin Playfair, who believes he is Sherlock Holmes, is examined by a psychiatrist (Joanne Woodward) named Mildred Watson. They meet as antagonists, form an uneasy alliance and drift toward romance, while Playfair seeks a rendezvous with the elusive Professor Moriarty. It may sound twee, and there are many on whom its gentle charms are no doubt lost, but it’s a funny, and surprisingly emotional, rumination on the relative insanity of a brilliant, harmless paranoid and of the increasingly mad society to which he is expected to conform. That last notion no doubt seems trite, but it has seldom been handled with such deftness and wit. Anthony Harvey, who also directed The Lion in Winter, shot the picture with a nervy energy that captures the New York City of the early 1970s, not as if under glass but as a living stage for Playfair’s intrigues.

Scott and Woodward tear into their roles with the relish of great actors who know in their bones they’ve got their hands on some of the choicest dialogue around, and the rich supporting cast includes Jack Gilford, Al Lewis, Rue McClanahan, Theresa Merritt, Eugene Roche, James Tolkan, Kitty Winn, Sudie Bond, Staats Cotsworth, F. Murray Abraham, Paul Benedict, M. Emmet Walsh and Louis Zorich. There’s also a brief but extremely effective chamber score by John Barry, arranged and augmented by Ken Thorne. Two home-video versions exist: One (a Universal Vault DVD) running under 90 minutes, reflects the theatrical release while the other, the television edit (on Blu-Ray from Kino Lorber) is longer, and includes the wry, delightful extended sequence in an immense Manhattan grocery store. It could, I suppose, be argued that the story doesn’t need the grocery sequence, and the climax plays well without it. But it also seems to me that the movie is enriched by its inclusion, and diminished by its excision. So, caveat emptor.

Dr. Mildred Watson: You’re just like Don Quixote. You think that everything is always something else.

Justin Playfair: Well, he had a point. ‘Course, he carried it a bit too far. He thought that every windmill was a giant. That’s insane. But, thinking that they might be, well… All the best minds used to think the world was flat. But what if it isn’t? It might be round. And bread mold might be medicine. If we never looked at things and thought of what might be, why we’d all still be out there in the tall grass with the apes.

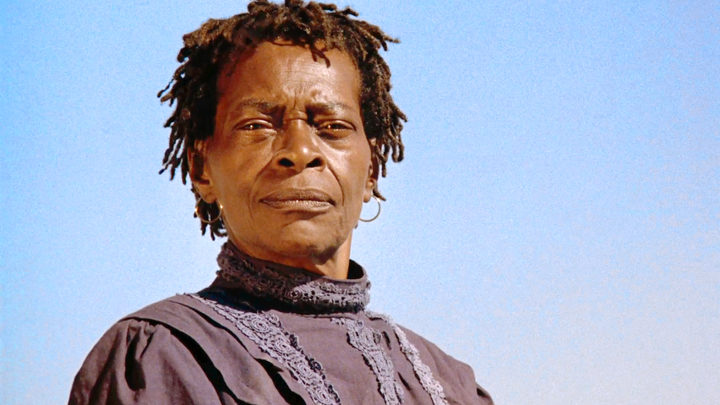

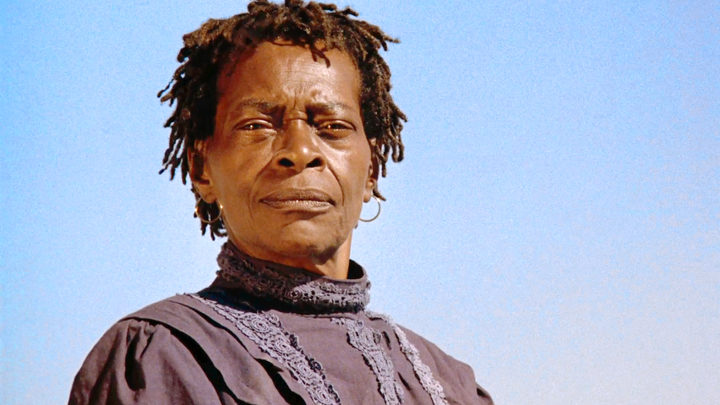

Cora Lee Day as Nana Peazant

Daughters of the Dust (1991) Julie Dash’s dreamlike evocation of Gulla society on a small South Carolina island in the early years of the 20th century was well-received critically but not a box-office success. 20/20 hindsight by knee-jerk commentators now has it that the picture was badly handled by its distributor because its writer-director was not only a woman, but a black woman. Yet I don’t see how this luminously photographed exercise in non-linear rumination could have been a popular success in any era: It’s so diffuse it seems less Impressionistic than merely undefined; we can scarcely tell what the various narrative threads are, much less what they mean. What’s best about the picture, aside from Arthur Jafa’s exquisite cinematography, are the wonderful faces of the expressive actors, especially those of Cora Lee Day as the family matriarch clinging to her African roots and religion, Cheryl Lynn Bruce as her overly-devout Christian granddaughter, and Barbara-O as her mirror opposite, a wayward young woman who left the island for a man but who now is involved with a younger woman. But 60 minutes into this hour-and-52-minute glorified student film my eyes had long since begun to glaze over and even those interesting faces weren’t enough to clear them.

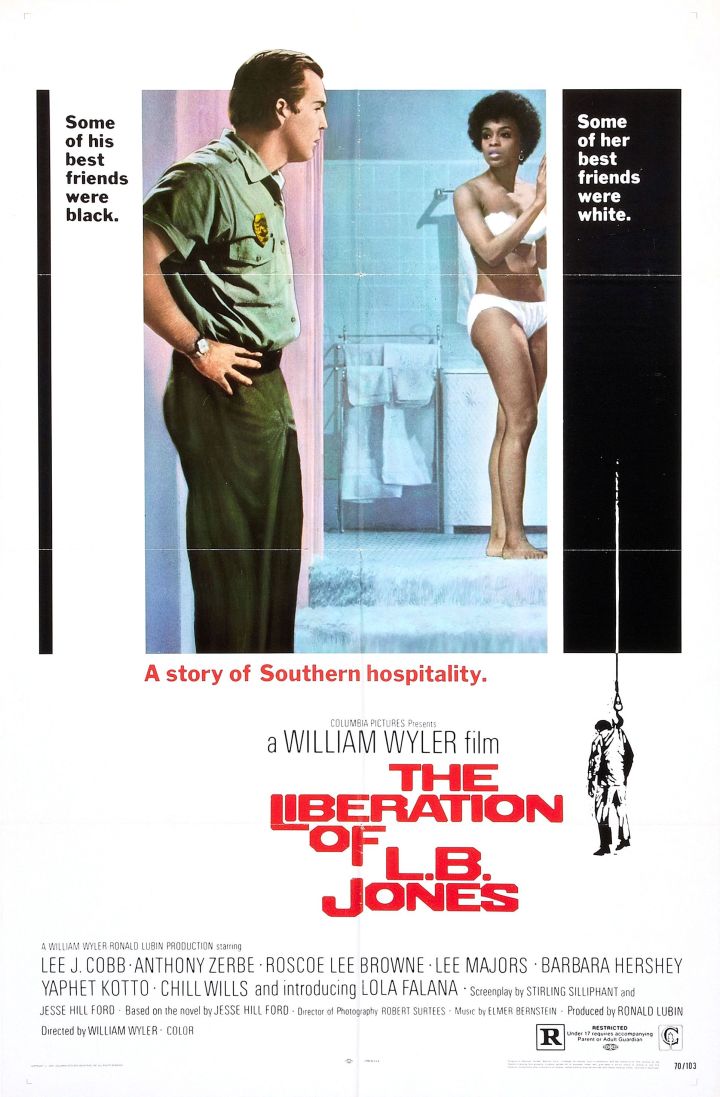

The Last Hard Men (1976) A tough, bloody Western from an unsparing Brian Garfield novel, starring Charlton Heston and James Coburn as old antagonists on a collision course. Although (unlike in the book’s ending) the movie’s climax seemingly leaves his character’s survival in doubt, and while the actor was too young for the role — as Garfield wrote it, the former lawman is in his 60s, and becoming increasingly frail — Heston is quite a good match for the ruthless Coburn, and the filmmakers (Andrew V. McLaglen was the director, and Guerdon Trueblood wrote the script) don’t flinch from the story’s most horrific moment, when the Heston figure’s daughter (Barbara Hershey) is gang-raped by Coburn’s team of escaped prisoners. The role of Hershey’s earnest suitor is the sort of part the young Jeff Bridges could have turned into a third lead by doing almost nothing, and while Chris Mitchum is attractive, he’s completely out of his depth; as an actor he was never much more than the pretty son of a movie star. While the performance of Michael Parks, as the sheriff who accompanies Heston on part of the quest to retrieve his daughter, suffers from his role being less interesting than in the Garfield book, the actors playing Coburn’s gang (Jorge Rivero, Thalmus Rasulala, Morgan Paull, Robert Donner, Riley Hill and especially Larry Wilcox and John Quade) are an impressively frightening bunch and Duke Callaghan’s widescreen cinematography is lustrous. Leonard Rosenman composed a terse, uncompromising score (it was later made available on CD) which was then replaced by a collection of newly-recorded cues from several of Jerry Goldsmith’s previous 20th Century-Fox titles — 100 Rifles (1969), Rio Conchos (1964), Morituri (1965) and the 1966 Stagecoach. I assume this was due to their being more traditional action cues and Western pieces than Rosenman’s dark, brooding compositions. But while they are splendid in themselves, if you’re already familiar with them from their sources they’re a needless distraction.

The great title card for one of “Jonny Quest”‘s creepiest episodes. If only the animation for the show had been this good!

“Johnny Quest“: The Complete Original Series (1964 – 1965) When I was a child the Saturday morning re-airings of this 1964 one-shot, an impressive attempt by Joseph Barbera and William Hanna to create and direct a weekly prime-time animated adventure series,‡ made an enormous impression. It was the first “serious” animation I’d ever seen, its often eerie plot-lines were, for a 5-year old, fascinatingly scary… and in the titular figure, the irrepressible blond-topped All-American Jonny, lay my first big crush.† The gifted comics artist Doug Wildey designed the show and its central cast: Plucky Jonny, his slightly mystical adopted Indian brother Hadji, father Benton Quest and bodyguard Race Bannon (who, white hair aside, was, somewhat confusingly for me, almost a dead-ringer for my own father). Produced in the so-called “limited” format pioneered by Hanna-Barbera, and which Chuck Jones astutely referred to as “illustrated radio,” the series, re-viewed from an adult perspective, contains highly variable animation; there are times when the characters are beautifully drawn, while at others they are remarkably poorly drafted, and this older viewer could certainly do with less of Jonny’s annoying little dog Bandit. But the stories are nearly always, despite a 26-minute limitation, well-plotted and exciting, often with an agreeable avoidance of earthly explanation for seemingly supernatural phenomenon. Children, like many of their adult counterparts, love to be frightened, and they especially love ghost stories and impossible monsters; it was a consistent reliance on rationality than killed my initial enthusiasm for the later H-B “Scooby Doo, Where Are You?”

Among the pleasures of the series were, and are, the voices, especially the appealing Tim Matheson as Jonny, the undemonstrably masculine Mike Road as Race, the charming Danny Bravo — who seems to have based his vocal characterization on Sabu — as Hadji, Vic Perrin as the show’s recurring villain Dr. Zinn and occasional guest artists such as Keye Luke, Jesse White, J. Pat O’Malley and even, astonishingly, Everett Sloan as an unrepentant old Nazi. Hoyt Curtin’s superb main title theme, with its bracing mix of big band and James Bond, is another asset; most of the incidental music is his, with additional and uncredited compositions by Ted Nichols. Many of the series’ best (and creepiest) episodes were written by William Hamilton: “The Robot Spy,” “Dragons of Ashida,” “Turu the Terrible,” “Werewolf of the Timberland” and “The Invisible Monster.” Among the others of especial note are “The Curse of Anubis” (Walter Black), “Calcutta Adventure” (Joanna Lee), and “Shadow of the Condor” and “The House of Seven Gargoyles” (both by Charles Hoffman). The recent Warner Archives Blu-Ray collection, while it contains few extras, looks terrific.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

† Like “Top Cat” and “The Jestsons,” “Jonny Quest” lasted only a single prime-time season. But when you’re a child, you’re not counting episodes, and due to repeated Saturday morning re-airings all three shows seemed to run forever.

‡How typical of me that my first big crush would be not another boy but a cartoon character… Still, I don’t know whether it was so much that I was attracted to Jonny as that I longed to be him. And isn’t hero-worship often what early same-sex crushes amount to?

Klute (1971) The truly chilling paranoia thriller starring Donald Sutherland and Jane Fonda, who as the call-girl Bree Daniels gives what I consider the finest performance by an American movie actor of the last 50 years.

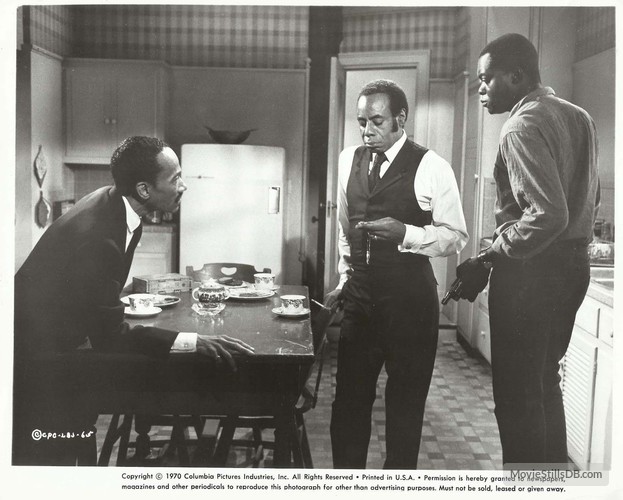

Rod Steiger, Jester Hairston and Sidney Poitier

In the Heat of the Night (1967) This tense, unblinking police procedural coated in a patina of social critique was one of the great successes of its year, which also saw the premier of Bonnie and Clyde. And while the picture is very much of its time in its examination of racist bigotry in the then-current American Deep South, it’s also a brisk, exciting detective thriller that holds up remarkably well, not least due to the crisp direction by Norman Jewison and to the picture’s precise Stirling Silliphant screenplay. Indeed, I prefer Silliphant’s creative adaptation to John Ball’s original novel, in which race is an important component, yet is less central to the narrative’s tensions than in the much bolder, angrier, movie, especially via the incendiary central relationship between Sidney Poitier’s Virgil Tibbs and Rod Steiger’s Chief Gilliespie. It should be remembered that the picture was in release only three years after the murders of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner, and the sense of dangerous rot and slowly simmering violence Jewison captures onscreen is as palpable as the oppressive, humid heat of its Mississippi setting. (Although most of it was shot in the southern Illinois town of Sparta.) Poitier gives a performance of wit, implacable inner strength and fierce integrity. There are a number of moments in the picture where what we see in a character’s face is more revealing, and quietly powerful, than what is said. Poitier has one such scene, when Steiger dismisses him, and his assistance in the murder investigation. Perhaps the most difficult thing an actor can do is to allow us to see him thinking. Too many actors project thought in those moments, and it’s nearly always phony. With Poitier, the impact registers itself in, first, his disbelief, followed by his fury, and, finally, a soft, subtle smile. He gets it; he’s been here before. Yet none of what we see is obvious, or overdone.

Lee Grant, as the widow of the murder victim, has a similar scene where, shocked into silence by the news of her husband’s death, she reacts against Poitier’s gentle attempt to seat her with an anguished, rigid gesture that slowly turns to acceptance and, more potently, the need to be comforted. It’s devastating to watch. As the racist sheriff, Steiger, at the height of his screen prowess, meets his co-star blow-for-blow. Gillespie is as much an outsider in the town as Virgil, and as distrusted by the locals. His tension is coiled deep, and he expresses that inner explosiveness in the way he compulsively chews gum, stopping only when he has something to say, or when comprehension breaks through his consciousness. The supporting roles are so perfectly cast they seem inevitable — absolutely real: Warren Oates as a patrolman with a secret; Larry Gates as a smooth and powerful old racist; the usually genial William Schallert as the bigoted mayor; Beah Richards as the local abortionist; Quentin Dean as a white-trash slut; Anthony James as a smirking creep; Scott Wilson as a prime suspect in the killing, whose changing relationship to Virgil is far warmer than what transpires between Tibbs and Gillespie; and Jester Hairston as an Uncle Tom butler outraged by Tibbs slapping his employer. (If you look sharp, you’ll also see Harry Dean Stanton as a cop.) That slap was a blow for liberty, and must have resounded sharply in many places across the globe, not merely the Southern United States. The dark, expressive cinematography is by Haskell Wexler — cheated by the constricted budget of a crane, he and Jewison make frequent, and often very effective, use of zoom lenses. Hal Ashby provided the fluid editing, and Quincy Jones’ score, mixing jazz and blues, has a nervous, funky energy perfectly in keeping with the movie’s sense of dark foreboding, and he composed a terrific main title song (with lyrics by Marilyn and Alan Bergman) that’s sung with passionate soul by Ray Charles. Jones’ cue for Wilson’s attempted escape (and suggested by Jewison) is a highlight, puttering out expressively as the murder suspect realizes he’s licked — the musical equivalent of a runner who’s out of breath.

Ghostbusters (1984) Horror comedy was far from a new concept when Ghostbusters was made — Harold Lloyd starred in something rather redundantly called Haunted Spooks in 1920 — but until 1981 and An American Werewolf in London there had never been one with elaborate special-effects, and even that was modestly budgeted; Ghostbusters cost six times as much (its budget was between $25 and 30 million.) Most of its predecessors tend to be either comedies with a few ghostly appurtenances (cf., Bob Hope’s The Ghost Breakers, Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, Young Frankenstein and Don Knotts’ The Ghost and Mr. Chicken) or genuine horror with black comedy overtones (The Abominable Dr. Phibes, Theatre of Blood, Phantom of the Paradise and, indeed, American Werewolf in London) but Ghostbusters takes nothing seriously. Its writer/stars, Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis, see everything as funny, and since The Ghostbusters themselves seldom panic, we spend the entire movie in a state of amused relaxation right along with them; the audience takes its cue from laid-back smart-ass Bill Murray’s Peter Venkman, for whom the entire natural world is a sardonic joke, so why should the supernatural world be any different? Murray’s comic persona is so relaxed he’s like a more sarcastic version of Bing Crosby.

The picture is inconsequential — you smile through most of it, even if you seldom laugh out loud — yet at the same time memorable; several of its set-pieces, phrases and gags became instant cultural touchstones, and after seeing the movie you’ll likely never look at a bag of marshmallows the same way. Sigourney Weaver has a good, serio-comic role as the woman whose apartment is being taken over by an ancient deity, Rick Moranis is sweetly oblivious as a dweeby neighbor, Annie Potts is the Ghostbusters’ preternaturally un-fazable secretary, William Atherton is an officious prick from the EPA (why do so many satires go after EPA rather than corporate polluters?) and Ernie Hudson gets a largely thankless role as the token black member of the team. László Kovács shot the movie beautifully, and the veteran Elmer Bernstein composed a score that, anchored to a loping main theme, was almost too effective: Despite his having composed in his long career everything from epics (The Ten Commandments) and Westerns (The Magnificent Seven) to thrillers (The Great Escape) and intimate dramas (To Kill a Mockingbird) and in every conceivable format from symphonic to jazz, the success of Airplane!, The Blues Brothers, An American Werewolf, Trading Places and Ghostbusters got him typecast for years as purely a comedy composer.

Touch of Evil (1958) Orson Welles‘ minor masterpiece, and the last time he was permitted the luxury of the studio system’s largess.

The Pink Panther (1963)

A Shot in the Dark (1964)

The Return of the Pink Panther (1975)

The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1976)

Revenge of the Pink Panther (1978)

The Trail of the Pink Panther (1982)

How Blake Edwards took his love for silent comedy routines deep into the post-War pop consciousness.

Chinatown (1974) The modern classic by Robert Towne and Roman Polanski.

Beetlejuice (1988) I misunderstood Beetlejuice when it was new; my contemporary review (fortunately now lost to the landfills) betrayed a certain — and to me, now, inexplicable — inability to keep pace with Tim Burton’s patented blend of amiability and dark comic outrage. It wasn’t that I couldn’t appreciate his often exhilarating blend of comedy and horror; the Large Marge sequence in Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure made me laugh so hard I nearly fell out of my seat. But I somehow wasn’t ready for an entire feature with that sensibility, unfettered. Revisiting Beetlejuice now, as I feel compelled to do every few years, I can’t help wondering why my younger self couldn’t relax enough to embrace such a cheerfully anarchic comedy as this one. Written by Michael McDowell (sadly, one of all too many creative men who succumbed to AIDS) and Warren Skaaren (also now prematurely dead, of bone cancer) from a story by McDowell and Larry Wilson, it’s a spook-fest for jaded children, a supernatural comedy that stints neither on the humor nor the paranormal.

As the nice young Connecticut couple who discover they’re dead and doomed to live with the wacko modern artist and her bourgeois real-estate developer husband they can’t scare away, Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis embody the spirit of the whole enterprise; they’re too sweetly gentle to make decent ghosts. As the titular “bio-exorcist,” Michael Keaton was a revelation, and his performance still amazes; nothing he’d done in movies up to that point had prepared us for the primal forces he unleashed in himself as Beetlejuice. His non-stop patter, loopy asides, gross-out wit and sheer brazen crudity were like nothing we’d seen in a movie comedy before. I think you’d have to imagine how movie audiences reacted the first time they saw the Marx Brothers to understand the impact that performance had on us in 1988. The strong supporting cast includes a very young Winona Ryder as the developer’s slightly off, death-obsessed teenage daughter; the peerlessly self-satisfied Jeffrey Jones as her father; the ever-treasurable Catherine O’Hara as his nasty, pretentious wife; Sylvia Sidney, in her of her final performances, as Baldwin and Davis’ case-worker, making the most of a role that is really little more than a delicious sick joke; Glenn Shadix as an obnoxious interior designer§; and Dick Cavett as a blasé society snob. Danny Elfman composed one of his brightest early scores, which deftly incorporates some of Harry Belafonte’s calypso hits. The first time I saw Beetlejuice, the use of “Day-O” offended me; now that sequence strikes me as one of the happiest in the picture. That’s one of the perks of revisiting old movies: Realizing that it wasn’t the original, uncategorizable, picture that was to blame for your dismissal of it, and being happy that you’ve lived to become a person who can surrender himself to it.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

§ Although Shadix’s performance struck me at the time as an exercise in extreme stereotype, the actor was himself gay.

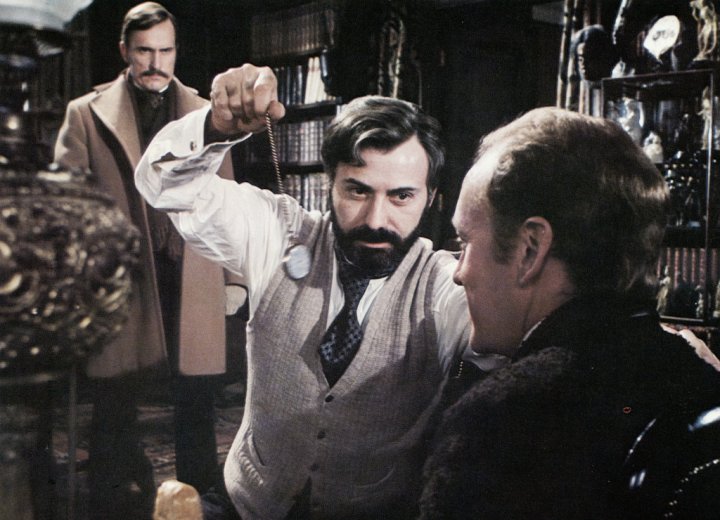

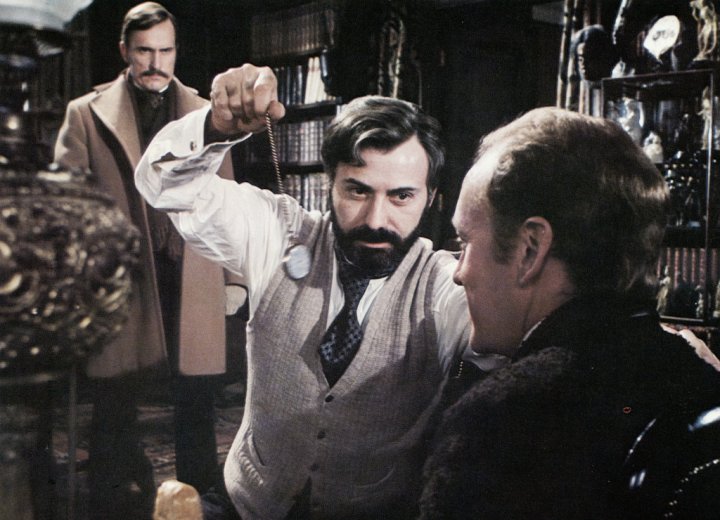

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976) Nicholas Meyer’s ingenious Sherlock Holmes pastiche.

Blackbeard’s Ghost (1968) I don’t know how I missed this one when it was released, as I habitually saw every new (or newly reissued) Disney movie, animated or live-action. It’s just possible it didn’t make it to the small Ohio town we were living in then, although every other children’s movie of the time did. In any case, I only discovered it when I came across the Disneyland soundtrack album — receiving the record for Christmas of 1970, I nearly wore it out through re-playing. It was my introduction to Peter Ustinov, who narrated it, and who starred as Blackbeard; the LP featured dialogue, mostly between him and Dean Jones, with a little Suzanne Pleshette shoehorned in, and I was entranced by Ustinov’s idiosyncratic way with a funny line, his ineffable charm, and (to borrow a phrase from Harlan Ellison in a different context) the “ineluctable rodomontade” of his florid verbiage. As I grew older and became more familiar with Ustinov, and with his performances and his work as a playwright and screenwriter, I began to suspect that he had re-written the Blackbeard script (or at least, his lines) as he had on Spartacus. And if you love Ustinov as I do, Blackbeard’s Ghost, while silly, generates a lot of laughter.

Although basing their screenplay on a very good children’s novel by Ben Stahl, in which two boys accidentally conjure up the shade of the pirate, still very much the bloodthirsty ghoul of legend, the movie’s writers (Don Da Gradi and Bill Walsh) ditched that premise in favor of pure comedy, making this far tamer Blackbeard’s more-than-reluctant compatriot the new coach of a hopeless college track team. That the coach is played by Jones is a help; whatever criticisms might be levied at the Disney pictures in which he starred, the actor (on whom I had a slight childish crush) always brought enormous conviction to them, and his outbursts of incredulous anger are as ingratiating as the engaging grin that occasionally splits his handsome face. The slapstick in the picture, directed with no special distinction by Robert Stevenson, is sometimes dopey and occasionally better than that, and the invisibility effects by Eustace Lycett and Robert A. Mattey are, as usual with Disney, well done, as are the lovely background matte paintings by Peter Ellenshaw. The screenplay has a pleasing lightness, enriched by what I again assume were Ustinov’s additions. The laughter the Disney Blu-Ray drew from me was considerable, even if nearly all of it was generated by Ustinov, who still makes me roar at lines I memorized off that record album when I was nine. Although Elliott Reid overdoes his bit as a television sportscaster, Pleshette is, as always, simultaneously biting and adorable as Jones’ inamorata; Joby Baker makes a good showing in the unaccustomed role of the villain; Elsa Lanchester gets a good scene or two as Jones’ dotty landlady; Richard Deacon is amusingly dry as the college dean; and Herbie Faye, Ned Glass, Alan Carney and Gil Lamb all have good bits in Baker’s restaurant-cum-gambling den. The plot revolves in large part around Blackbeard’s old home, maintained as an hotel by his descendants, little old ladies with nothing else to cling to. I mention this because one of them — and I have no idea which — is identified on the imdb as Betty Bronson. That’s a name more forgotten now than it was 50 years ago, but 45 years before, that Bronson was enchanting youngsters as the screen’s first Peter Pan. I would like to think that Walt Disney, one of whose final productions Blackbeard’s Ghost was, knew that, and gave the old trouper a job. Anyway, it would be pretty to think so.

Anna Kendric sings “On the Steps of the Palace,” my favorite number in Stephen Sondheim’s dark/light score. “He’s a very smart Prince / He’s a Prince who prepares / Knowing this time I’d run from him / He spread pitch on the stairs…”

Into the Woods (2014) Although I have been a Sondheim fanatic since discovering the Company cast album in 1976, and while the original production of Into the Woods was the first Broadway musical I saw before its cast recording had been released, I deliberately avoided the movie of it when it was new, on the basis of two proper names with which it was associated: Disney, and Rob Marshall. Perhaps only in Hollywood could a minimally talented hack like Rob Marshall reap such rewards (and a-wards) by removing the guts from ballsy musical plays like Chicago and Nine. After countless producers and screenwriters, including Larry Gelbart, had worked at it, what was Marshall’s great “break-through” on Chicago? Turning all the musical numbers into dream-fantasies Renee Zellweger imagines. If you have to justify why people are singing and dancing in a musical, why the fuck are you making a musical? Still, with a screenplay by James Lapine, the original book writer and director of Into the Woods, perhaps there was only so much damage Marshall could do to it. Well, it was someone’s brilliant idea to cast the magnificent Simon Russell Beale as the Baker’s Father and then butcher his role so completely he’s left with no songs and only a couple of lines, confusingly delivered, since we can’t tell who he is, whether he’s real or a phantom, and haven’t any idea whether his son (James Corden) knows either; and to let Chris Pine as an 18th century prince sport a trendy two-day growth of beard on his chin.‖ The picture looks splendid, which I attribute largely to its cinematographer (Dion Beebe), set decorator (Anna Pinnock), costumer (Colleen Atwood) and production designer (Dennis Gassner). And it’s largely well cast, with actors who can sing: Corden; Meryl Streep, sardonic but subdued as The Witch; lovely Emily Blunt as The Baker’s Wife; cute Daniel Huttlestone as a full-throated Jack; Lilla Crawford as a foghorn-voiced Little Red Riding Hood; Johnny Depp as her Wolf; Tracey Ullman as Jack’s Mother; and Anna Kendrick who, although attractive only from a single angle… and that one her director seldom favors… is an otherwise charming and effective Cinderella. Into the Woods was significantly better than I’d expected. Yet I still tremble whenever I hear another name yoked with this director’s: Follies. Hasn’t that poor show suffered enough?

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

‖As my friend Eliot M. Camarena once asked, do people like that when they’re children announce, “When I grow up, I wanna look like Fred C. Dobbs!”?

The Art of Love (1965) A surprisingly brainless affair to have come from the typewriter of the witty Carl Reiner, riding high in 1965 with the deserved success of “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” which he created and oversaw, and for which he wrote many of the most memorable early episodes. The best thing about this moderately black farce concerning a failed American artist in Paris whose supposed suicide instantly drives up the prices fetched for his work by his duplicitous best friend (James Garner) is Van Dyke as the artist. His comedic timing, seemingly boneless body and inimitable way with a line or a situation are the equal of the great comedians he worshiped, and it’s one of the ironies of modern history that he came along at a time when movie and television comedies were so often loud, witless and inane. Had Blake Edwards not already collared Peter Sellers and Jack Lemmon, what a find Van Dyke would have been for that fellow student of slapstick!

Reiner can’t really be blamed for the general dopiness of the movie, since he was working from an existing story by two other writers (Alan Simmons and William Sackheim) and the movie’s young director, Norman Jewison, doesn’t appear to have been a great deal of help to him. The Art of Love is attractive to look at — it was shot by Russell Metty — but inert, marking time with things like Angie Dickinson’s fainting shtick (it’s funny the first time), Elke Sommers’ perpetual innocent act and the braying of Ethel Merman, apparently cast as a madam just so she could belt out an instantly forgettable nightclub number. The usually ingratiating Garner has little to play here but his character’s cheesy self-centeredness, and Reiner stoops to such things as plunking a cartoon Brooklynite Yiddishe couple (Irving Jacobson and Naomi Stevens) in the middle of Paris. Still, Jay Novello has a couple of funny bits as a nervous janitor and little Pierre Olaf does miracle work as an umbrella-toting police detective, Cy Coleman provided a perky score (with additional music by Frank Skinner), and DePatie-Freleng came up with some modestly amusing main title animation. There’s little excuse, however, for a comedy — especially one with Dick Van Dyke — whose only big laugh comes at the very end, and absolutely none for its indulging in such feeble wheezes as the periodic introduction of a Madame Defarge-like hag, complete with knitting needles, who shows up every now and then to screech her delight at Garner’s impending execution. But at least I now understand what my mother meant when she once told me that after seeing this one on television when I was a boy I walked around the house for a week saying, “Guillotine! Guillotine!”

Murder by Decree (1978) That Sherlock Holmes occupied a revered, albeit fictional, place in the same late Victorian Britain that saw the appalling murders in Whitechapel has intrigued Sherlockians for decades. What more natural meeting could there be than between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s brilliant consulting detective and “Saucy Jacky,” as that figure of horror known popularly as Jack the Ripper styled himself in a letter to the papers? Derek Ford and Donald Ford (the former known primarily for his snickering sex comedies) imagined Holmes investigating the murders in the 1965 A Study in Terror, and the same year in which this more recent attempt was released saw the publication of Michael Didbin’s dark little novel The Last Sherlock Holmes Story, very much concerned with Jack. The elements are there even in the mind’s eye: The dimly gaslit cobblestone streets, the hansom cabs and private cabriolets, the enveloping fog that swallows up forms, faces and screams of terror and pain. That Bob Clark, the onlie begettor of Porky’s should, of all people, have directed as beautiful a fiction as Murder by Decree is as puzzling as his making that evocative adaptation of Jean Shepherd, A Christmas Story. But then, as Orson Welles once told Bogdanovich, “Peter, you only need one.”

The literate screenplay by the playwright John Hopkins emphasizes a more riant, and more passionate, Holmes than is the norm, and Christopher Plummer could scarcely be bettered in the role as the filmmakers, if not Conan Doyle, conceived it. His performance reaches two peaks, one infinitely quiet (his reaction to Geneviève Bujold’s heartbreaking madwoman), the other bristling with outrage at what his betters (including John Gielgud as the Prime Minister, unidentified in the picture but clearly made up to resemble Robert Gascoyne-Cecil) have been up to. Hopkins also, blessedly, gives us a Watson who is as far from the Nigel Bruce model as can be imagined. And while the irreplaceable James Mason is a bit hoary for the role, his aplomb is undeniable; a moment of especial charm is the way he expresses dismay at Holmes, and with a look of genuine hurt, when the former squashes the lone pea on the doctor’s plate. And if he is occasionally the voice of hidebound Empire, Mason’s (and Hopkins’) Watson is also equally as capable of wit as Holmes as, for example, when Sherlock asks his compatriot why his friend deems him only “the prince of detectives” and wishes to know who is king. I won’t spoil the joke here, nor the conclusion of this intricately plotted exercise, based on some theories by Elwyn Jones and John Lloyd in their contemporaneous book The Ripper File.

The exceptional cast includes a starchily smug and imperious Gielgud; the wrenching Bujold; Frank Finlay as an uncharacteristically deferential Inspector Lestrade; David Hemmings as the police inspector in charge of the case (and who bears absolutely no relationship to the very real Frederick Abberline); Susan Clark as a heartrending Mary Kelly; Anthony Quayle as the dangerously reactionary Sir Charles Warren; Peter Jonfield as a chillingly psychotic chief villain; and Donald Sutherland as the shaken spiritualist Robert Lees, who believes he’s seen the Ripper. Despite a few unnecessary visual flourishes, Clark’s eye is nearly unerring, abetted to an exceptional degree by the rich and expressive cinematography by Reginald H. Morris and the astonishing production design of Harry Pottle; I don’t know whether Pottle is responsible for the staggeringly effective matte paintings of London used in the picture, but whoever painted them, they put you absolutely there. The only real miscalculation in the movie is the highly derivative musical score by Paul Zaza and Carl Zittrer from which I heard distinct liftings from John Williams (the scene in Jaws of Richard Dreyfus investigating Ben Gardner’s boat), Jerry Goldsmith and Bernard Herrmann (those eerie strings) and Richard Rodney Bennett (the opening sequence of Murder on the Orient Express) and in which — aside from the plaintive traditional Irish tune for Mary Kelly — there is little that is either original, interesting, useful or pleasing to the ear.

Text copyright 2019 by Scott Ross