By Scott Ross

As with anything in life, from a pleasing odor to a symphonic masterwork, there are movies that, encountered at an especially vulnerable moment emotionally, can resonate with you for life, and that merely thinking about return you to a time and a place when you were, if not happy, at least hopeful of happiness. A Little Romance, for me, is one of those works of popular art that while perhaps less than perfect (exactly what is?) retains its sweetness and its charm and more than justifies my long-ago fondness for it. Seeing it again transports me instantly, as the madeleine does to Proust’s narrator, although I suppose evoking À la recherche du temps perdu when one hasn’t read it is the very definition of pretension. Given the (largely) Parisian setting of A Little Romance, however, I may be excused having been caused to think of it.

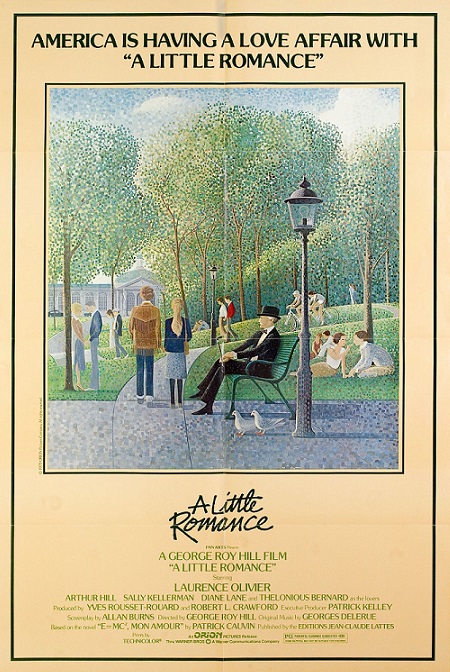

I should preface this little piece with the intelligence, hardly surprising to anyone who knows me or has read even superficially among the essays on this blog, that I have a soft spot for whimsy, particularly charming romantic whimsy — although the whimsy also has to have wit; Finian’s Rainbow is almost infinitely more delicious a fantasy than Brigadoon, due less to its ridicule of racism and sharp critique of capitalist culture than because E.Y. Harburg and Burton Lane were wittier, and lighter on their feet, than Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe.* No matter how cynical you may think yourself at 18 — and I thought I was cynical as hell — hope is built into youth, and romanticism is an adjunct to hope. Against the evidence of my senses and forebodings, when I first saw A Little Romance with the one I loved, I still thought I had a fighting chance with him. I was predisposed to want to see the movie because George Roy Hill was attached to it, and Laurence Olivier, not to mention Sally Kellerman and Arthur Hill. And since my… whatever he was, or imagined himself in relation to me… was a Francophile, going to see A Little Romance together was more or less a foregone conclusion.

Hill, aside from having made both Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting, pictures I’d seen and loved in reissue, also directed the 1964 Nora and Nunnally Johnson-written comedy The World of Henry Orient, which had absolutely charmed me when it was broadcast on NBC in the mid-’70s. His work with adolescents in that movie augured very well for this one, and I was not disappointed. Hill could be a prickly and even perverse director (see Julie Andrews’ puzzled, and puzzling, description of him in her book Homework repeatedly endangering her life with fire while making Hawaii) but he seemed, by and large, to have an affinity for actors, and especially young ones. The amused manner with which, in Henry Orient, he depicted the teenage Merrie Spaeth and Tippy Walker and their obsessive assault on the private life of their concert pianist idol (Peter Sellers) also celebrated the pair’s youthful exuberance and was in sharp contrast to the usual run of movies about kids, then and now, which wink at their audiences and, whether adolescent or adult, comfort their prejudices, simultaneously condescending to, and being condescending toward, them.

Hill’s work with the two young actors here is every bit as incisive, perhaps more so. As Lauren, the object of Thelonious Bernard’s affections, Diane Lane in her first movie role is utterly enchanting (Olivier called her “the new Grace Kelly,” although she was only 13) and there is not a frame in the picture in which she seems to be acting or a line that sounds false in her mouth. When she smiles, spontaneously, her adorable, slightly leonine young face lights up everything around it. Much the same holds true of Bernard, who was not an actor and whom Hill reportedly took into his home for a month learning both acting and English, with results I should imagine as miraculous as those in evidence following the intense weekend Moss Hart spent in 1956 turning Andrews into an actress. You’d never guess, watching this boy, especially in his scenes with Lane and Olivier, that he was anything other than an actor. By which I do not mean that he exhibits artifice. Quite the contrary: Bernard’s is one of the most natural performances by an adolescent in movie history. The qualities these two young people exhibit together convince you of their characters’ love for each other, and their delight in each having found a kindred spirit in a world that doesn’t know quite what to make of their highly individual intelligence.

There’s another enticing name in the credits aside from George Roy Hill: That of the screenwriter, Allan Burns. Although I first became aware of him in the early ’70s via his credits on “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” which he created with James L. Brooks,† Burns also worked with Jay Ward on “The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show,” “Dudley Do-Right” and the peerlessly bizarre “George of the Jungle,” and with Brooks on “Room 222” and “Paul Sand in Friends and Lovers.” He was a master at finding the comedic slant and (aside anyway from his cartoon work, and “The Munsters,” which he also created, and where this doesn’t obtain) translating it into recognizable, if distinctly, and distinctively, quirky reality. He did beautiful work here adapting the Patrick Cauvin novel E=mc² mon amour, which while containing more than the seed of the movie’s plot, is, perhaps because it alternates between Lauren’s narration and the boy, Daniel’s, and is thus related solely in their adolescent voices, annoying. Among other things, Burns cuts down on the interminable number of times Daniel says (or writes) “Bingo!” and at least, in a clip from the 1975 Burt Reynolds cop picture Hustle, shows us where he might have gotten the expression.

Some commentators thought at the time, and many still think, that the American movie-besotted Daniel’s viewings of The Sting and Butch Cassidy were placed in A Little Romance out of Hill’s own vanity. But Daniel’s affinity for Robert Redford comes directly from the novel… although I personally cannot comprehend the youth’s predilection for the actor; no boy I knew in my teenage years cared that much about Redford one way or another. While we admired him, and may have enjoyed his movies, certainly few of us considered him a great or important actor. If we had favorites they tended to be the quirky ones, often ethnic, like Richard Dreyfuss, Richard Pryor, Al Pacino, John Travolta, Gene Wilder, Dustin Hoffman, Paul Newman, Jack Nicholson and even Woody Allen. Redford was little more to us than a gifted, goyishe sex symbol, and even the gay kids I knew mostly thought of him as physically desirable, not as especially interesting for his performing; I knew Streisand freaks and early Midler fans, but no one who was gaga over Redford. (Clint Eastwood was popular too, of course, and although his movies of the period tended to be dumb “hick pix,” even Burt Reynolds was more of a presence to us, largely because of his obvious good humor.)

I seem to be knocking Redford as an actor, and I don’t mean to. He’s seldom bad, and there are nearly always moments in his movies in which he is splendid: I’m thinking especially of the nod he gives Newman in Butch Cassidy after admitting he can’t swim; the way he finally flares up at Hal Holbrook’s intransigence near the end of in All the President’s Men; how he expresses Hubbell’s pleased embarrassment at having his story read in class in The Way We Were; that laugh of his at the end of The Sting; or indeed his entire performance, which I regard as his best, as Parritt in the television Iceman Cometh. But I never responded to him the way I did, say, to Newman or Jack Lemmon, with that keen anticipation which is the primary component of pleasure at the movies. Redford on screen is in some essential way just too amiably bland to be great, or to inspire a young cineaste.

In any case, Hill wasn’t the project’s original director, and the movie includes another reference to Redford, in Three Days of the Condor, which the young lovers try to see but are turned away from, and there are long clips as well from True Grit and The Big Sleep in the main title montage showing Daniel exercising his cinematic obsession.‡ (That last is also crucial to his reaction to Lane when he discovers her character’s name is Lauren, like Bacall, of whom she is ignorant.)§

If there is a real self-referential element for George Roy Hill in A Little Romance beyond those disputed movie clips, it’s that Sally Kellerman, as Lane’s mom, and married to Arthur Hill, is having an affair with the obnoxious American movie director played by David Dukes, which parallels the way Angela Lansbury cuckolds Tom Bosley with Peter Sellers in The World of Henry Orient. As Kellerman’s husband (and Lauren’s stepfather) Hill is kindly and gentle, and much more interested in and supportive of his stepdaughter than the corresponding character in the novel, and in this way he resembles Bosley in Henry Orient. Taking off from Daniel’s love for movies, this plot element allows him to meet Lauren on a film set, even as he expresses contempt for Dukes as a filmmaker. (The character’s name, George de Marco, could be meant as a dig at Brian De Palma.) Giving the movie’s only poor performance, Dukes overdoes de Marco’s smirking machismo, but so does Allan Burns; it’s not impossible to imagine a man being so creepily insinuating about the 13-year-old daughter of the woman he’s involved with as de Marco is of Lauren, but it is difficult.

Much more important to the A Little Romance than these adults, however, is another: Laurence Olivier as Julius Santorin, the elderly gentleman pickpocket who unwittingly sets the plot in motion by telling Daniel and Lauren of a lovely Venetian legend that, “if two lovers kiss in a gondola, under the Bridge of Sighs, at sunset, when the bells of the Campanile toll, they will love each other forever.” (The way Olivier delivers this line contains the essence of his aging charm.) The kids believe him because they need to, and because it fuels their exhilarated romanticism, and their desire to enact the legend dates the picture like nothing else in it; today Daniel and Lauren would simply look up the “legend” online with their Smartphones, and there would be no movie.

Daniel is immediately suspicious of Julius, and we sense he’s jealous of how charmed Lauren is by the old man; like every lover, he wants to be the only light in his beloved’s life. When Julius is forced, en route to Venice, to admit to the kids what he is and that the legend is one he himself concocted and Daniel lashes out at him for his “damn lies,” the old reprobate is un-fazed. “What are legends anyway,” he ripostes, “but stories about ordinary people doing extraordinary things? Of course, it takes courage and imagination… not everybody has that.” That sly prod is of course designed to goad the boy, and it does. Julius knows how to prick the balloon of Daniel’s adolescent male vanity, and his obsession with movies, as when he admits that his stories about his deceased wife Emilia are part of his own elaborate fantasy:

Julius: She was an attempt to bring a little romance into my life.

Daniel: That’s pretty sad!

Julius: Any sadder than sitting in a darkened theater, pretending you are Robert Redford, performing heroic deeds?

I was an unadulterated fanatic about Olivier at the time this movie was released, and while I am much more critical of him now than I was then, there were few things about going to the movies during my own adolescence I appreciated more than the opportunity to watch this old knight savor a mildly witty line as if it was a pearl out of Sheridan, and his reactions to the events surrounding him were often the best things about the movies he was in. He has a moment in A Little Romance when Julius reads something insupportable in a newspaper that is among the greatest comic effects of its age: Not only is the open-mouthed sound of shock he makes utter perfection; just the way he grips the paper is hilarious.

My one real complaint about the picture, aside from the de Marco character, is when, under questioning, Julius is struck by the angry French police inspector (Jacques Maury) investigating the disappearance of Lauren and Daniel. Even supposing he suspects the old felon of harming the lovers, the facts of Julius’ record should be enough to convince him than an elderly thief with no history of violence does not suddenly become a kidnapper, or a killer of adolescents. Did we really need to see that sort of violence against a frail old man?¶

Nearly everything else about A Little Romance works, and works in a way that seems — at least the first time you see it — both surprising and inevitable. Hill’s direction is smooth and limpid, and what you most remember from his movie are the people in it, and what they do. This is almost a lost art now, when battering an audience has become a substitute for engaging it. The lovely color cinematography by Pierre-William Glenn, while capturing the beauty of France and Italy, never descends into postcard prettiness, and William Reynolds’ editing is crisp without being agitated.

I wish Sally Kellerman had more screen time; although the story doesn’t really allow for it, she’s such a unique presence on the screen that she injects a delicious jolt of energy into everything she does. Lauren’s mother is a mass of paranoiac guilt and prejudice (she projects onto Daniel what de Marco is doing with her) and, one assumes, as bored as she is privileged. Yet as Kellerman plays her she may be ridiculous but she’s too amusing to be hateful. As Lauren and Daniel’s young friends, the smilingly phlegmatic Graham Fletcher-Cook and the wonderfully gawky Ashby Semple, whose only film this was, are splendidly cast and Broderick Crawford has a witty role as the star of the dumb thriller movie de Marco is shooting in Paris. As bewildered American tourists, Andrew Duncan and Claudette Sutherland are marvelous — funny without tipping into caricature.**

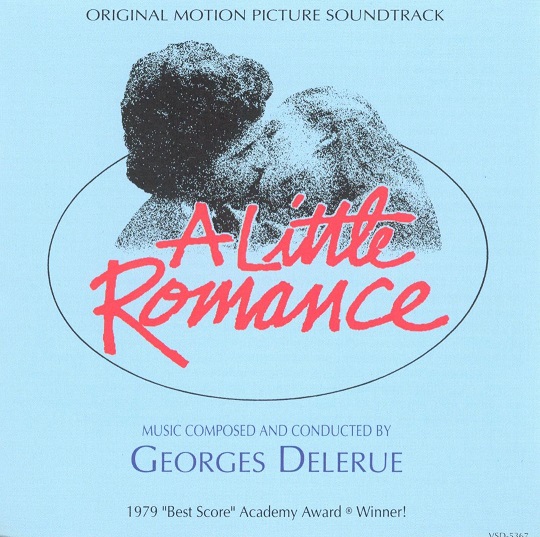

Arguably the movie’s greatest asset, after its script and its cast, is the nearly perfect Georges Delerue score.†† The favorite composer of François Truffaut (Delerue scored nearly all his movies from Shoot the Piano Player to Confidentially Yours) and Jack Clayton (The Pumpkin Eater to The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne) Delerue’s hallmark was a gift for lyricism that, despite his ability to write spirited comic and exciting thriller music, is what marked his particular genius. Here, in addition to a beguiling main theme as well as a vivacious tune for the lovers’ travel, Delerue relied for his romantic writing on the Largo from Vivaldi’s Lute Concerto in D, which bathes Lauren and Daniel in wistful optimism. (As with the Joplin rags in The Sting, the Vivaldi was Hill’s idea.) When the two — spoiler alert, as they now boringly say — must part at the end, the reprise of that melody becomes nearly unbearable, and by the time George Roy Hill gives us the emotional release of Thelonius Bernard’s leap up into the unforgettable freeze-frame with which the movie ends and that suspends the boy in an attitude of joyous hope, it would take a stronger emotional constitution than mine not to be moved.

Had I known at 18 what I do now, I’d have likely been even more cynical than I was in 1979. But when I was young and it was new, A Little Romance completely fulfilled my ideal of satisfying romantic whimsy.

The ache the movie elicits from me now may be infinitely more bittersweet. The satisfaction remains.

*And is it just me, or when you’ve said or written it often enough, doesn’t “whimsy” sound like it should be the name of a girl in a J.M. Barrie play? Just me, huh?

†It’s been said that children don’t read, or at any rate pay attention to, movie and television credits, and in my case that was true until I hit puberty and became genuinely interested in theatre and motion pictures, who played what in them and who wrote (but seldom, interestingly, who directed) them.

‡Hearing John Wayne dubbed into French is the single best argument I know against the practice; if perhaps the most famous and identifiable actor’s voice aside from Humphrey Bogart’s and Cary Grant’s is not an essential part of his screen performances in the rest of the world, then movie stardom itself means nothing.

§Curiously, the screenwriter and the director of A Little Romance replicate an error Cauvin made in E=mc² mon amour when Daniel says to Lauren, “Call me Humphrey” — a name Bogart only used for his billing — when the correct phrase would have been, “Call me Bogie.” The novelist, being French, may perhaps be excused for this, especially since he also didn’t seem to know that Bogart’s pet name for Bacall was, famously, neither “Lauren” nor even (her real name) “Betty” but “Baby.” Daniel, being a movie fan, would almost certainly know better. The filmmakers should have as well.

¶Speaking of frailty: Hill rigged a special motorized bicycle for Olivier, who had been ill for some time, to ride during the race that becomes a crucial plot point. Olivier rejected it; when Julius is cycling in his wobbly, terrified fashion, what we see is not a double, or a fake, but the real thing. It makes one feel even warmer toward that fearless old trouper.

**Sutherland is best remembered, at least by musical theatre aficionados, as Smitty in the original of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, in which her peerless reading of a single Frank Loesser quatrain, on seeing that the dress she’s got on another woman is wearing (“This irresistible Paris original/Tres sexy, n’est pas?/God damn it, voila!/And I could spit!”) is among the funniest performances ever captured on an original cast recording.

††After nearly 30 years of exquisite scores, this one got Delerue an overdue Academy Award, and precipitated his move from France to Hollywood. He died there, at the shockingly young age of 67, in 1992.

Text copyright 2020 by Scott Ross

Great review! I love this movie! Definitely a childhood favorite. You are absolutely right about Bob Redford (by the way, my wife thinks he is the blandest actor ever!). I’m only a couple years younger than Bernard and Lane, and I never thought Redford was “cool.” Steve McQueen or Paul Newman, but Redford? I don’t think so! 😉

Thank you, Eric. I hadn’t watched this movie in decades. It was lovely to see how well it holds up. Speaking of Redford, what he did to Bill Goldman on “All the President’s Men” is a good illustration of what a NICE man he is…

By all accounts, Redford seems like a decent chap. I just find him a little boring. But he is brilliant in President’s Men, and I also love him in films like The Candidate, The Way We Were, etc.

I loved this movie, just wonderful. Still love Diane.

i loved this movie the first time I saw it and have watched it many times over the years.

It’s truly charming and Lane, Betnard, and Olivier are absolutely flawless in it. I love the nusical score as well.

My only sadness about it is that a sequel was never made in follow-up to see Lauren and Daniel as young adults and if they did truly stay in love and be together forever.

Maybe even two sequels, as they aged??? If any movie cried out for a sequel, it’s this one! Ah, one can dream . . . 🤩