By Scott Ross

Until quite recently, what I knew of The Liberation of L.B. Jones (1970) was limited to a few basic facts: Of its being William Wyler’s final movie as a director; of its starring one of my favorite actors, the late Roscoe Lee Browne; of its financial failure; and of its dealing, in some way, with what is prettily called “race relations” in the South of the late ‘60s. Thanks to a kind friend, I have finally seen the picture, and it left me deeply depressed.

No, scratch that: Depressed, and angry. This is due, not to any failings on Wyler’s part, or those of his screenwriters, Stirling Silliphant and Jesse Hill Ford, on the latter of whose novel The Liberation of Lord Byron Jones — a better title — the movie was based. I was instead disheartened by the action. Not because I found it unrealistic or clichéd but because I found it all too real. I am angry in part because I had been led, by capsule reviews, to think the picture was well-meaning but inert, and infuriated as well (if only in retrospect) by the movie’s negligible box office at the time of its release. But mostly, I am both angry and depressed because what this movie, now 45 years old, depicts is not simply, or merely, America Then. Remove the period clothing and music, and the casual use, in public as well as private, of the word “nigger” (we’re subtler now) and what The Liberation of L.B. Jones depicts is America Now.

America Then, in this story, is the South, and the country generally, in which a distinguished black man, a pillar, as they used to say, of his community (or, more to the point of this story, a “credit to his race”) can be cold-bloodedly murdered in the dark of night and his body mutilated, the crime covered up and the assassin, a white police officer, not only free but never charged or in any way acknowledged. America Now is the nation in which a black man or woman of any sort and condition can be gunned down by a cop or a private citizen, even in front of witnesses, be posthumously smeared by the press and blamed for his or her own murder, the crime “investigated,” and the killer never charged. Or, if charged, and (even more rarely) tried, acquitted.

Do you begin to understand the reasons for my rage?

America Now is America Then, Redux. And with a vengeance.

Lynching, in case you hadn’t noticed, is back. And expressing the racially insupportable, has re-emerged as a game any number can, and does, play, often in screeching decibels, every day since January of 2008. Barack Obama is hated, not merely for the unforgivable sin of being a Democrat and winning the White House, twice — nor indeed for any of the reasons he should be deplored. No, this man has the temerity to not merely be the leader of the other party: He also has the unmitigated gall to be a Negro! (That he is also half-white is largely ignored, although one can imagine the mere contemplation of that hideous act of miscegenation committed by his parents also informs the rage of the bigoted. That he is also a neoliberal — in his own estimation, a “moderate Republican” and no friend to progressives or, Scandinavian prizes notwithstanding to peace, is, typically, twisted by these types, who perennially screech, with no supporting evidence whatsoever, that he is in fact a Marxist.) Even those of us who despair of Obama’s corporatist leanings, his war-mongering and his serial lack of spine, feel compelled to defend him, more often than not, and despite our discontent, if only because the voices on the other side are so often and so stridently, hideously, bare-facedly those of unregenerate racists, freed now (at last! at last!) from the need to be polite, or covert, in their prejudices. One can be forgiven, in 2015, for wondering whether the 1960s and ‘70s ever even happened. I’ve begun to suspect we dreamed the entire era.

While racism is never entirely dead, certainly I never thought I’d see a return to such overt ugliness on a day-to-day basis, in my lifetime. The Presidency of Barack Obama has in some weird way allowed what had to be kept either silent, or behind firmly closed doors, a re-emergence into the sunlight. One has the feeling that some white, “Christian” Americans (a minority and not, as Democrats never tire of trying to make you believe, the majority of the Republican party) have been silently steaming for years, forced by law and politesse to swallow their fury at being unable to voice their xenophobia, and that all it took to overcome their reticence at expressing their contempt for everyone else — the restrains that frowned on their being able to call a spade a nigger — was the assumption to the Presidency by a man of mixed race.

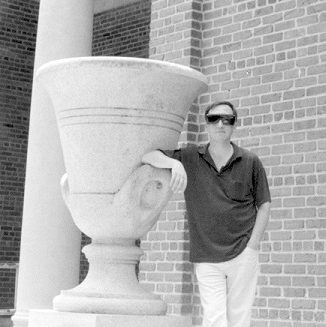

Willie Joe Worth (Anthony Zerbe) confronts L.B. (Rocoe Lee Browne) in the latter’s kitchen.

The dilemma that faces L.B. Jones, in the unassailable person of Roscoe Lee Browne, is whether a man may stand up and be a man without being lynched. In a key moment, he recalls seeing a black picketer threatened by a white mob and running, to the jeering accompaniment of “Run, nigger, run!” Surely someone, someday, must refuse to run, and not be lynched. At the emotional climax of the movie, L.B. makes the conscious decision, remembering that taunt, to stop running… and discovers the fatal truth that reason does not prevail. His crime — his willingness, in divorcing his unfaithful wife (an act his racist white lawyer refers to as his “liberation”) to publicly air her prolonged affair with a white policeman — simply cannot be countenanced. What is done to L.B. is so revolting even the white cop (Anthony Zerbe) is sickened, and resolves to turn himself in. He is saved from this foolishness by L.B.’s own attorney (Lee J. Cobb), a prominent man haunted by his youthful affair with a young black woman. He is troubled, not by the affair itself, to which he freely admits, but by the, for him, unconscionable fact that he had begun to see her as a person.

L.B. with his friend Benny (Fayard Nicholas) and the vengeance-driven Sonny Boy Mosby (Yaphet Kotto).

That there is some retribution, directed at Zerbe’s partner (Arch Johnson) via the intervention of Yaphet Kotto’s Sonny Boy, and that it, like L.B.’s murder, goes unpunished, provides, not comfort but a modicum of dramatic satisfaction. Yet it cannot mitigate the horror, particularly in the ironic light of Sonny Boy’s own, earlier, decision to bury the past. The present, however, is not so forgiving. The movie begins and ends with Kotto’s unreadable face, and this is telling.

William Wyler on the set. Center: Roscoe Lee Browne; right, Lee J. Cobb.

Wyler’s direction of The Liberation of L.B. Jones was, at the time, considered half-hearted, even cold. The failure to appreciate the craft, honed over 45 years, with which he approached this incendiary material, is also telling. In a cruel sort of irony, Silliphant, the co-scenarist of this picture, was also the screenwriter of the much more popular, lauded, and awarded In the Heat of the Night (1967). It takes nothing away from that robust time-capsule entertainment to note that The Liberation of L.B. Jones does not end with the racist toting LB’s suitcase like an unconscious Redcap parody, the crime neatly tied up and the rifts, if not mended, at least sufficiently patched.

In this picture of America Then, there is no comfort. And in that way, too, the movie all too clearly reflects America Now.

Text copyright 2015 by Scott Ross