By Scott Ross

Note: This is essentially a re-post of an earlier essay. One of the original images had inexplicably dropped off and the new WordPress “Blocks” system made it impossible for me to re-edit the post without altering and damaging it. Consequently, I have reassembled it here. I also discovered I had mis-attributed some artwork to Amsel which I had thought, in some cases for years, he drew (or in the case of the “The Seven Percent Solution” poster, completed) and have either removed them or amended their entries accordingly.

As before, most of these images, and much of the information, are from Adam McDaniel’s lovely Amsel tribute site.

Richard Amsel’s artwork, evocative of earlier eras but infused with a modernist’s wit and self-conscious sense of style, graced the posters for many of the iconic American movies of the 1970s. His magazine cover art, for TV Guide especially, shimmered and his book covers gave his subjects an eloquence to match their own contents. Although he died, a casualty of the AIDS pandemic, at the obscenely early age of 37, his best work is a timeless reminder of his own, particular and unduplicable, genius.

I first encountered this signature, as distinctive as the work it ornamented, on the poster art for Murder on the Orient Express in 1974. It became a talisman for me; whenever I saw it, I could feel reasonably sure of a rich visual experience to accompany the signature.

This, almost unbelievably, is the work of the 18-year old Amsel, for his high school yearbook, in 1965:

An early self-portrait.

I. Magazines

Amsel created a number of covers in the 1970s and early ’80s, often for TV Guide. Here, a delightful dual portrait of Carol Burnett and her gifted alter-ego, Vicki Lawrence:

Amsel’s study for a cover portrait of Lucille Ball, commemorating her retirement from regular series television (left), and the completed cover (right). As glorious as the finished product was, some hint of soul was lost in the process.

Amsel: “I did not want the portrait to be of Lucy Ricardo, but I didn’t want a modern-day Lucy Carter either. I wanted it to have the same timeless sense of glamour that Lucy herself has. She is, after all, a former Goldwyn Girl. I hoped to capture the essence of all this.”

He did.

Valerie Harper as Rhoda. Amsel captures both the actress and the character’s quirky and stylish clothing choices.

Sometimes the color balances on these beautifully rendered covers were distressingly off by the time the magazines hit the newsstands (ask your mother) and checkout aisles. Here is the art for two such: Hepburn’s ill-advised network television debut as a Connecticut Yankee Amanda Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie, and the telecast of Gone with the Wind.

Two beautiful Amsel portraits, for a cover story on John Travolta and the premier of Shōgun, respectively:

Other magazines: Note the Klimt hommage on the first GQ cover, left.

The then-current movie of The Great Gatsby did well enough at the box-office, thanks one presumes, to Redford’s presence, but its real impact was on fashion and style. Images from, and costumes for, it were almost ubiquitous in the popular magazines of 1974.

Lily Tomlin, for the cover of Time. She was then starring in her hit Broadway debut, Appearing Nitely. Amsel, having very little time to create this, drew on a photo of Tomlin used in conjunction with the show and added stars to illustrate that the funny youngster from Laugh-In who did Ernestine and Edith Ann had fully arrived.

II. Music

Amsel art for the front-and-back covers for two RCA Victor This is retrospective LPs from the early 1970s.

Appropriately enough for a young gay man in the ’70s, Amsel was drawn to two of the three big diva icons of the time. Here, Barbra Streisand in the oddly appropriate style of Gustav Klimt:

The cover of the Divine Miss M LP.

Amsel’s artwork for Bette Midler’s 1975 Clams on the Half-Shell Revue: Miss M as she might have been seen by Vargas.

The Divine Miss M in her most archetypal portrait. A New York friend who was there tells me, “This was 6 stories high on The Palace Theater in Times Square.”

Midler à la Alphonse Mucha. Artwork for the Songs for the New Depression LP.

Midler’s once-indispensable backup trio, The Staggering Harlettes.

III. Books

First, the Not-Amsels. Although I previously attributed to Richard Amsel the covers for two of the better paperback movie books of the early 1970s (Leonard Matlin’s Movie Comedy Teams and Marjorie Rosen’s Popcorn Venus) if I’d looked more closely I would have seen that the art for both of these distinctive, nostalgic pop-art designs were signed “Meisel.” You can see, I think, why I was so easily mistaken. There was a fashion illustrator (and, later, photographer) called Steven Meisel but Adam McDaniel informs me that this Miesel was Ann, “a classmate and friend to Richard Amsel.” (Thanks, Adam!)

Now for some genuine Amsel: First, for one of Peggy Hudson’s annual Scholastic Books television season run-downs. Note the psychedelic late-’60s visuals. Like, too mod!

The marquee will eventually read Act One: An Autobiography by Moss Hart. Interestingly for an account of an allegedly heterosexual man’s teenage years and early youth, and despite the leading lady here who seems to have eyes only for Mossy, there are no women to speak of in this justly famous theatrical memoir; Hart never mentions girls at all.

The clenched-fisted-men-against-the-world renderings by Amsel of Hart and George S. Kaufman are rather odd.

For a fascinating study of Fitzgerald’s Hollywood years (hotly refuted by Tom Dardis in his contemporaneous Some Time in the Sun) an appropriately shattered Scott, anchored by the Gatsby-esque figure at the bottom.

The unholy marriage of Mucha and Klimt: Sacred (Duse) and profane (Madams.)

Amsel’s cover art for The Madams of San Francisco without the text. Note the cursive signature and, arguably, the Bob Peak influence.

Also in modernist mode, Amsel’s cover for an early ’70s reissue of Romola de Pulszky’s 1934 biography of her husband Vaslav Nijinsky. The “major motion picture,” originally planned by the James Bond co-producer Harry Saltzman to be written by Edward Albee, directed by Tony Richardson and to star Rudolf Nureyev and Paul Scofield, would have to wait until later in the decade, when none of the principals would still be involved. More on this anon.

The “star” portraits are surprisingly undistinguished, but Amsel’s depiction of Selznick captures his intensity, his anxiety, and his essential alone-ness.

IV. Movie Posters

Here is the area in which Richard Amsel carved his most indelible niche, and made his deepest impact. He was doubly lucky to be working when he was. First, in the rich period of poster design before the photographic montage or single image completely supplanted hand-drawn poster artwork and, second, by creating exhibition illustration during the last great period of American movies during which, while some glamour still existed, taking a dramatic chance was de rigeur.

Hello, Dolly!: Amsel captures the “Gay 90s” feeling, filters it through late 1960s pop- and op-art and adds a Mucha headdress (with Spirographed flowers!) to promote a musical that nearly broke its studio. If only the movie itself had exhibited half as much joyous life as Amsel’s artwork for it.

An early Amsel poster, for the German release of a cultural landmark.

Amsel’s first poser art for Robert Altman. The real saloon-door plank on which it’s painted and the carved filigree to either side capture the Western setting while the portraiture suggests the quirky nature of the leads in this, one of the late filmmaker’s true masterpieces.

Amsel’s jokey portrait of Burt Reynolds here is a humorous nod to his then-recent Penthouse centerfold and the total picture a canny evocation of Frank Frazetta’s crime-caper comedy movie posters of the 1960s. (For those familiar with the Ed McBain 87th Precinct novels, Yul Brynner, at extreme left, played The Deaf Man.)

A slightly (Bob) Peak-ish study, for What’s Up, Doc? Amsel limns both the oddball romance of the thing and its classic face nature (the keys.) Top: The color version of the complete drawing. Bottom: A variation, cleverly bifurcated to represent the keys to the co-stars’ San Francisco hotel rooms. Streisand should have hired this man to be her full-time portraitist; she seldom looked more radiant than she did in one of his drawings.

Another one of those “If only the movie had been as distinguished” Amsel posters. That’s Ava Gardner in the background, as Bean’s unwitting inamorata Lily Langtree.

Variations on a theme: First, the superb Amsel image for Irvin Kershner’s underrated adaptation of the Anne Roiphe novel about a young married New Yorker ruefully contemplating her latest pregnancy through a series of wild fantasies and starring a non-singing Barbra. Note the integration of the star’s surname in the title. (And which should have forever ended the mispronunciation of it as “StreiZand,” but didn’t.) Second, the TIME magazine parody version.

One of Amsel’s most memorable designs, evoking the Saturday Evening Post of the 1930s.

Amsel based his concept for The Sting on J.C. Lyendecker’s “Arrow Collar” ads. That Lyendecker used his male lover as a model adds an interesting, if unintentional, twist to what was perceived by some critics as the movie’s un-articulated homoerotic undercurrent. (Adam McDaniel created this comparison image for his original Amsel website.)

A lovely Amsel image for the last Lerner and Leowe musical, best remembered for Gene Wilder’s sweetly uncanny Fox and Bob Fosse’s marvelous “Snake in the Grass” sand-dance in the desert.

Although I’d seen Amsel’s work before, his brilliant design for the Paul Dehn/Sidney Lumet adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express in 1974 was the first of his posters to completely capture my attention. It’s all there: The evocation of 1930s design, the starry cast, the train and even the murder weapon, its filigreed hilt beautifully incorporated into the image of the engine. Wouldn’t this make you want to see the movie? It certainly persuaded me. I still consider this one of the finest examples of the poster designer’s art in all of movies.

A splendid Amsel design for the Stanley Donen mis-fire Lucky Lady starring the third of the era’s big movie/musical divas. If the picture had been half as good as this…

An Amsel concept design for Nashville. Note that he captures the 24 main characters, the country-and-western milieu, and the sense, despite the seemingly amorphous quality of the complex narrative arc, that something is about to explode.

Amsel’s superb artwork for the writer-director Robert Benton’s nifty, semi-comic meditation on the hard-boiled L.A. gumshoe genre starring Lily Tomlin and Art Carney as a very sane kook and the aging shamus she hires.

The Shootist, John Wayne’s final movie. One dying legend playing another: Glendon Swarthout’s terminally ill gunslinger John Books, framed by Amsel faces on a gold and sepia base. (From top left: Richard Boone, Hugh O’Brien, Ron Howard, Sheree North, Lauren Bacall and James Stewart.)

Amsel’s original design for Voyage of the Damned (right) and the release poster (left), in which Janet Suzman’s image (at lower right) was replaced by that of Katharine Ross. A great, agonizing subject undone by tepid filmmaking and overwhelmed by too-starry a cast. On the other hand… Where are the comparable faces today who could fill out that cast-list?

From top left: Orson Welles, Malcom McDowell, Faye Dunaway, Max von Sydow, Oskar Werner, James Mason, Lee Grant, Helmut Griem, José Ferrer, Janet Suzman, Julie Harris, Fernando Rey, Dame Wendy Hiller, Ben Gazzara, Sam Wanamaker, Maria Schell, Michael Constantine and Suzman/Ross. (Not depicted: Denholm Elliott, Nehemiah Persoff, Leonard Rossiter, Victor Spinetti, Luther Adler and Jonathan Pryce!)

Amsel evokes Fin de siècle Vienna (and again, appropriately, the lithographs and jewelry designs of Alphonse Mucha) in his original poster art for Nicholas Meyer’s marvelous Sherlock Holmes pastiche The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. (From left: Nicol Williamson, Laurence, Olivier, Alan Arkin, Vanessa Redgrave.)

The final poster, re-designed and re-drawn by Drew Struzan, omits the woman’s arm and tempting cup (I’m not sure why Amsel included that, since the Redgrave character is being drugged by injections of cocaine, not deadly pots of tea) as well as Olivier’s Moriarty, keeping only his eyes, misterioso, at the center. Struzan also moves Redgrave to the top and refashions her, but essentially retains Amsel’s renderings of Williamson and Arkin.

Amsel’s glorious design for Julia. Jane Fonda’s Lillian Hellman is central, but is dominated by both Jason Robards’ Dashiell Hammett and Vanessa Redgrave’s eponymous figure — less distinct, and idealized, as Julia is for Lillian.

Striking concept art of Robert DeNiro and Liza Minnelli for Martin Scorsese’s ill-fated (and rather ill-conceived) New York, New York. The final poster used a photo of the stars.

Concept art for the pointless Farewell, My Lovely follow-up, and the completed poster. Mitchum as Marlowe; note that his mussed hair in the poster suits him better than the pompadour, as does the more lined, saggy face. Candy Clark in the Martha Vickers role clings, damsel-in-distress-like, to Chandler’s iconoclastic private detective and looks much more frightened in the finished work. Despite the great cast and the filmmakers’ hewing close to the novel, it’s a lousy movie — when you’ve seen Bogart and Bacall, directed by Howard Hawks, why bother? But that’s a terrific design.

Death on the Nile. It’s a variation on Amsel’s own Murder on the Orient Express design, but then the movie — charming and witty as it was — was a bit of a re-tread too. Still… what I wouldn’t give to see all of these actors alive and kicking again! (From top: Peter Ustinov, Maggie Smith, David Niven, Jack Warden, George Kennedy, Olivia Hussey. Mia Farrow, Bette Davis and Angela Lansbury.)

Un-used Amsel art for a forgotten Sylvester Stallone epic. One of the reasons, aide from his… shall we say, limited acting palette?… Stallone had to keep making Rocky and Rambo movies: His “big” brainchildren had an unfortunate tendency to flop, as this one did. That Felliniesque design does make you want to see the movie, though. And that’s what poster design is supposed to be all about.

The Muppet Movie. Another un-used concept design, and another picture for which Amsel’s artwork was supplanted by Struzan’s. Nonetheless, he captures the joy of the Muppets’ first picture, along with its highest moment (which came, unfortunately, right at the beginning): Kermit singing “Rainbow Connection.”

Sally Fields’ break-through movie performance, as Norma Rae Webster. The more well-known poster featured a photo of Fields triumphant, but Amsel’s portrait more nearly captures her anxieties and social class.

The unused concept for the eventual movie of Nijinsky. The golden-hued ballet designs emphasizing Nijinksy’s defining roles almost overwhelm the central figures (Leslie Browne, George de la Peña and Alan Bates.) Note de la Peña’s headband and damp locks, suggesting the sweat behind a great dancer’s art.

The completed design emphasizes the (so-called) love triangle, gives de la Peña sculpted prettyboy/matinee-idol hair, and opts for a single dance: Nijinsky’s L’après-midi d’un faune.

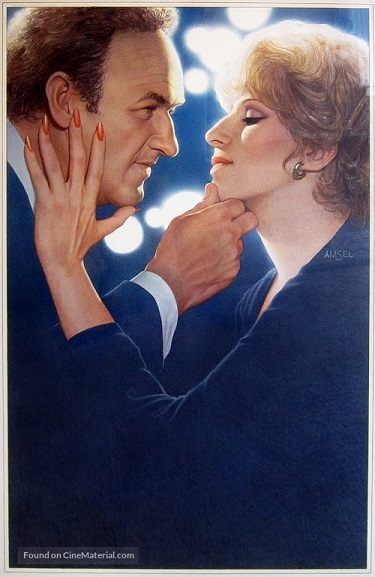

Amsel’s art, based on a lobby-card photo image, for the wonderful 1981 comedy All Night Long: Gene Hackman and Streisand moving into a clinch. Ironically, considering how much more acclaimed and popular than Amsel he has since become, the final poster art was by Drew Struzan… and it gave entirely the wrong idea about this charming comic romance, making it seem to unsuspecting audiences like a raucous sex-farce.

Amsel invokes 1930s screwball comedy, as well as the Damon Runyan characters, for this forgotten 1980s remake, written and directed by Walter Bernstein. Sort of makes you want to shell out your $3.50 to see the movie, though, doesn’t it? Indeed, now that Matthau and Curtis are gone and Andrews is an old lady I can’t help wanting to see it, on a big screen, even at three times the original admission price.

Amsel’s superb design for the George Lucas/Steven Spielberg/Lawrence Kasden Raiders of the Lost Ark, capturing the sepia-era quality of those movie serials that inspired it, the derring-do and brooding nature of Harrison Ford’s Indiana Jones, and the main desert setting. Left: The un-edited design. Right: The completed poster.

The reissue poster: Nothing makes a man smile faster than a monster box-office hit. Note Ford’s newly exposed chest and suggestive crotch-bulge.

Lily and Amsel, together again: Art for Jane Wagner’s comedic remake The Incredible Shrinking Woman. (Yeah, I know Joel Schumacher directed it. But in the beginning was the word.)

Amsel was commissioned, by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, to create this gorgeous design for the restored, rereleased version of A Star is Born. The pose is from the movie (“Here comes a big, fat close-up!”) and was used in the original 1954 ad campaign. Amsel emphasized the spotlights, added the stars and a made a slight change to Garland’s costume. Compare this with the original: Amsel’s “Vicki Lester” somehow has a greater sense of yearning.

Amsel captures an emblematic moment in American pop-culture for the laser-disc release of The Seven Year Itch. An elegant presentation of what is in fact Billy Wilder’s only truly bad movie. Even Kiss Me, Stupid is better.

Amsel’s design for this Graham Greene adaptation incorporates a portrait of Michael Caine: The eyes of God, watching the lovers. The picture is also known as Beyond the Limit, as though Greene had written some sort of fast ‘80s kiss-kiss/bang-bang techno-thriller rather than a typically thoughtful examination of the cynical political murder of a minor functionary.

La Streisand, as Yentl. You can see why Struzan’s work is so often mis-cited as Amsel’s.

Richard Amsel died just as his style of design was being phased out by the Hollywood studios in favor of the far less rich (but, presumably, much cheaper) photo-image that now dominates the American movie poster, to the detriment of the movies and the sorrow of those who valued an art that was once universal. And, for reasons that are for me somewhat inexplicable — perhaps due to his rock LP covers, or the fact he was associated, peripherally, with Star Wars… or just because he’s straight? — the fine but far less inspired Drew Struzan has gotten much more press in the last couple of decades than the almost infinitely more gifted Amsel, on whose work Struzan appears to have drawn, or was at the very least heavily influenced by. I’m not, by the way, knocking him for that; all creative people are affected by the work of those who precede them. I simply feel that Struzman’s is less distinctive and original than Amsel’s, and less praiseworthy.

We who love Amsel’s work can only express our deep thanks to Adam McDaniel for carrying the burden, and the illuminating torch, through efforts which include not only his splendid website (and his design of a square honoring Amsel for inclusion in the AIDS Memorial Quilt) but also a documentary and a celebratory book, both in the works, and godspeed the day. Thank you, Adam.

Special thanks as well to Amsel’s friend the late Bob Esty, for inspiring me to collect here, and comment on, these magnificent works of popular art.

Revised text copyright 2020 by Scott Ross