By Scott Ross

It’s tempting to wonder what the fate of Zodiac might have been had it been made, say, 25 or even 15 years earlier. (Although if it had been, it wouldn’t be the same picture.) A few of the best movies of any given year perform dismally at the box-office, of course; who, in their time, saw Make Way for Tomorrow or Dodsworth? There was a period, however, and not so long past, when it was exceedingly rare that a film this good — even great — was seen by so few people. Today, chances are it won’t get made at all, or will be produced only on a marginal budget, or with compromises that cripple its very originality and essential integrity, and still few serious moviegoers will partake of it.

Among its many remarkable achievements, Zodiac absolutely recreates the look and feel of its places and times. This was achieved to a certain degree with strikingly seamless CGI — one of the very few instances in recent memory of computer imagery serving the movie rather than, as is the overwhelmingly usual case, the other way around. But, as with any complex work of art, the reasons Zodiac succeeds so well as a motion picture are manifold, set off by four distinct, intelligent decisions.

There is, first, the determination of its filmmakers — the screenwriter James Vanderbilt, the producer Brad Fischer and the director David Fincher — to treat the material without sensationalism, excessive gore or pat conclusions. Since no definitive guilt has ever been established for the killer, or killers, responsible for what became known in the late 1960s and early 1970s as “the Zodiac murders” in and around San Francisco, the filmmakers (as with Robert Graysmith, the author of two related books on which the picture was based) can only speculate, and that, in the case of the movie, without absolute conviction.* Second, the creative team’s centering their story not on Zodiac but the effect of his (their?) killings on several people associated with the case either directly (the detectives Dave Toschi and Bill Armstrong and, to a lesser degree, the crime reporter Paul Avery) or indirectly (Graysmith himself, and his young family.) Third, their laudable determination to eschew dwelling on the murders themselves in favor of sharp, shocking indications that disturb as much as, if not more than, more explicit illustration would have. And, finally, their equally salubrious decision to concentrate on the unsettling ripples with which these unsolved, violent crimes penetrate, not merely the surface but the essential core of those who become, as Graysmith and Toschi do, obsessed with them.

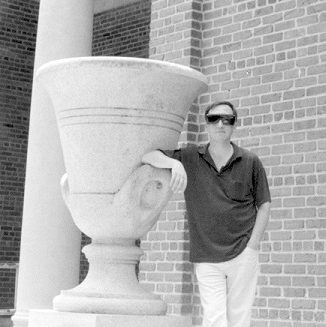

Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal) really knows how to show a date (Chloë Sevigny) a good time.

Indeed Graysmith, a Chronicle cartoonist at the time of the murders and not even a reporter, becomes so enraptured by “Zodiac” that obsession is almost too polite a word. Although Toschi too is deeply committed to solving the cases, he has other work to do, and does it. Avery’s situation is altogether more pitiable; after being directly threatened, the flamboyant, arrogant reporter becomes (in the movie, anyway) by turns, easily startled, furtive, and increasingly alcoholic. In some terrible way, the filmmakers suggest, Paul Avery was Zodiac’s last, unclaimed, victim.

It’s perhaps no accident that Zodiac is among the best-cast movies of its time, just as All the President’s Men was in its: Fincher reveres, as I do, that 1976 investigation by William Goldman and Alan J. Pakula into Watergate and its eventual (alleged) decoding by Woodward and Bernstein. Too, the starkly lit look of the Chronicle in Zodiac echoes the visualization of the Post in the Pakula picture, and Graysmith stands in well for “Woodstein,” notably during his nocturnal adventures, which share something of Robert Redford’s occasionally frightening experiences. Jake Gyllanhaal does well by Graysmith despite being, in my experience of his work, utterly incapable of convincingly playing a heterosexual. He’s outshone considerably by Mark Ruffalo’s alternately charming, affable and no-nonsense Dave Toschi, and by Robert Downey, Jr.’s superbly illuminated Paul Avery. Equally impressive, in less spectacular roles, are Anthony Edwards as Toschi’s partner Bill Armstrong; Chloë Sevigny as Graysmith’s eventual second wife; John Carroll Lynch as the prime suspect, Arthur Leigh Allen; Brian Cox in a marvelous turn as that appalling fame-whore Melvin Belli; and the always interesting Phillip Baker Hall, splendid as the SFPD’s handwriting expert. Charles Fleischer, the once and future Roger Rabbit, contributes, in what just may be the most hair-raising sequence in the movie, a small miracle of a cameo as an oxymoronically bland yet ineluctably sinister cinema manager.

The distinctive manner in which Dave Toschi (Mark Ruffalo) wore his service revolver was immortalized by Steve McQueen in Bullitt. He was also the reluctant inspiration for a very different sort of San Francisco cop, Eastwood’s Dirty Harry Callahan, whose initial picture was a thinly-disguised Zodiac knock-off. (Anthony Edwards at left.)

Charles Fleischer as Bob Vaughn, in the movie’s most unnerving scene.

There are, to be sure, a few aspects of Zodiac that either puzzle unnecessarily, or which are inconsistent. (An inconsistency may be minor and still confuse.) Why, for example, when Graysmith says he has two children, do we only see one, until he remarries? Further, we don’t know why he’s single, or how he has custody of his young son. Is he divorced? Widowed? And where is that other child? The puzzles are more problematic. Why is so little made, for example, of the physical differences between the killer (or killers) at Vallejo and Lake Barryessa and the suspect in the murder of San Francisco cabbie Paul Stine? The former are said to have been committed by a very large man, possibly bald, or at least with lank hair, the latter by a smaller man with a crew cut, whose clothing, moreover, was not noticed to have been spattered with blood. This is no small matter; much of the endless speculation about the case hinges on such disparities. Indeed, Graysmith and others speculate that The Zodiac may have worn wigs to disguise his appearance, something James Vanderbilt’s screenplay does not address — or, if it did, the reference was cut. You can easily disguise your hairstyle, but altering your physique, and your height, are knottier (if not necessarily insoluble) problems. Additionally, for a movie as scrupulous and intelligent as this one, there is rather too much reliance on accepted theories about Zodiac. Some strong questioning of circular thinking may have been in order here.

The banality of evil? John Carroll Lynch as Arthur Leigh Allen at the climax of Zodiac.

According to Fincher, one of the edits the studio insisted upon before release of the 157-minute theatrical cut (his own runs 162) was the elimination of one of its more compelling sequences, available in the so-called “Director’s Cut” on DVD and Blu-ray, in which Toschi and Armstrong rattle off to an unseen magistrate their reasons for seeking a search-warrant via speaker-phone, and await the answer. Since Fincher was emulating in Zodiac, both for his cops and for Graysmith, the slogging labor Woodward and Bernstein go through in All the President’s Men — the scene echoes the lengthy one in ATPM in which Pakula holds on Redford at his desk as he juggles telephone calls as well as the later, crucial scene in which Bernstein and his informant misunderstand each other — this mandated omission is doubly irksome. It points, once again, to the real problem facing the serious American filmmaker today: How does one cope with an increasingly impatient and sub-literate audience which, in addition to being unable or unwilling (if not indeed both) to follow a reasonably complex narrative, is accustomed to, and demands, a thrill-a-minute approach to everything it sees, with grand mal seizure-inducing cutting to match?

John Simon concluded his original, rave review of the Jason Miller drama That Championship Season by noting that if this play failed, Broadway itself deserved to die. Zodiac, as far as I am concerned, says the same thing about American movies. That a film this good could not find a substantial audience, and did not succeed in pecuniary terms, indicates that the current Hollywood too deserves death, and the sooner the better.

*Graysmith has many critics, and his certainty that Arthur Leigh Allen was the Zodiac is shared by none of them. That other investigators have, in the years since his books were published, pretty much gotten Allen off the hook does not mitigate against the excellence of the movie based on them.

Text copyright 2014 by Scott Ross

Post-Script: April 2014

I neglected in the above to make mention of two additional aspects of Zodiac that contribute so mightily to its effectiveness: Its look, and its score, both effectively bifurcated. The look is the work of the late Harris Savides, the picture’s cinematographer, who gave it two, equally distinctive aspects, of light and of dark: The muted glow of its Northern California exteriors by day and the deeply unsettling blankness of its many night sequences. The score is comprised largely of pop songs of the period that serve as guideposts to their times, and partly by David Shire’s minimalist chamber accompaniment. (That he also memorably scored All the President’s Men is surely not coincidental.) Shire’s music owes something to Herrmann’s for Psycho but only in passing; the rest is the nearly unerring genius of a composer who has been utilized far too seldom by American filmmakers but whose scores are, without exception, splendid. Fincher’s alternating use of period Top 40 items like “Easy to be Hard,” “Soul Sacrifice,” “Jean” and “Baker Street” place the scenes squarely within their chronology and, occasionally, add more than a frisson of atmosphere. Indeed, a movie can alter the songs themselves: I can virtually guarantee that after seeing Zodiac you will never hear Donovan’s “Hurdy-Gurdy Man” in quite the same way.