By Scott Ross

If you care about literacy, reading almost anything these days is taking your sanity in your hands on a regular basis. And it isn’t just the utter codswallop that passes for political “thought.” If you’re a regular reader of books, you can’t believe the idiot errors even good, established writers commit. First you re-read the line, or the claim, or the comment, thinking, “I can’t have read that right.” Then you realize: “My God! I did read that right!” One is sometimes left dazed, wondering how the hell people can get basic, well-known facts so horribly wrong… and when the voice of the editor will once more be heard upon the land.

Books about the movies have always been problematic in this area. I started reading them when I was 12 or so and becoming a seriously movie-mad adolescent, and even at that age I was occasionally nonplussed by the poor scholarship (and the equally atrocious writing) in much of what I read. And what is worse, those errors quickly get replicated by know-nothings, and repeated in their own books, which then influence equally lazy minds in the laity. Some time ago Leonard Maltin discovered to his horror that Hollywood studios were depending on his annual TV Movies reference guides for the running-times of their own films, making him feel that if he didn’t get it absolutely right, he’d somehow be responsible for the consequences of the suits’ laziness.

As so many of us have had occasion to note in reference to appalling and easily-corrected misstatements in print, in the age of the Internet it takes, quite literally, 30 seconds to perform a search, and usually less than two minutes to get an answer to matters of trivia you are unsure of. (Always assuming you are not so sunk in reactive, neo-Luddite conservatism as to actually pull down a physical book from the shelf to find the information. But then, on the evidence of You-Tube videos, I assume bookcases are now for displaying knickknacks, awards, small plants and, if the host is especially pretentious, a tiny stack of paperbacks lying on their fronts.) Of course, in a by-gone era, one depended not only upon good and diligent writers to ferret out these facts but on equally good editors to catch the mistakes and correct them. Magazines like The New Yorker used to have fact-checking departments (o, that phrase!) renowned for being impossible to fool. Now you routinely read statements in the pages of that once-venerable publication that make you scream in plaintive despair.

My own favorite example of the past decade, in a profile of Billy Joel, was the claim by the writer that one of Joel’s Long Island neighbors was John Barry, “the man who wrote the James Bond theme” when Monty Norman’s authorship of the Bond theme precipitated two of the most famously litigated cases of press libel in movie history. Barry once asked the professional ignoramus Terry Gross, in answer to her question concerning Norman — years after those lawsuits, both of which Norman won and about which Gross, all too typically, had her usual half-assed knowledge — why, if he didn’t write it, the producers hired him to score all those other Bond movies? Uhhh… because on Dr. No Barry saved Norman’s good-but-not-great theme with his terrific arrangement of it? To throw that spurious argument back at Barry, if Norman didn’t compose it (which he demonstrably did)* why is he listed as the composer on soundtrack record labels and liner notes, and in Bond movie credits? Why has he won two libel actions against publications in Britain which he claimed defamed him by suggesting he was not the theme’s composer? Far be it, however, for a New Yorker features writer to spend ten minutes doing research before making an ignorant claim. One which, mark me, children, will be repeated.

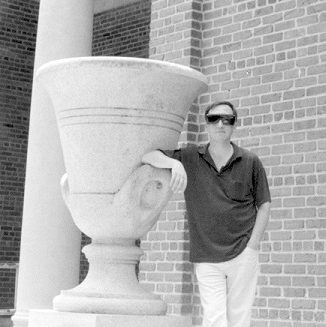

Charles Ward, presumably in Dancin’

Which brings me, finally, to the point. The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood (Flatiron Books, 2020), Sam Wasson’s latest flawed foray into movie history, shares with its immediate predecessor, Fosse (Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014) editorial propensities by its author to elide, omit and, occasionally, obfuscate that are discomfiting. I’ve had my problems with Wasson in the past over issues that, while minor, nevertheless concern the conscientious reader. I’m not referring to questions of style, or even approach, both of which are matters of personal taste and neither of which affect the essential truth of what is written. What does matter are being honest, and not making the sorts of errors that cause your better-informed readers to blanch. In Fosse, for example, Wasson asserted, without attribution (and in a book whose source-notes were voluminous) that Ann Reinking and the dancer Charles Ward were having an affair during the Broadway run of the 1978 Fosse revue Dancin’, in which she starred and he was featured. It is, and was, well known that Ward was gay; indeed, he was one of the early theatre figures to contract AIDS. It is true that Reinking was sharing an apartment with Ward at the time, but it’s quite a leap to assume they were romantically involved, even if Fosse, in his paranoia, believed they were… or Reinking, to spark his jealousy, told him they were. In any case this is, as far as I am aware, a baseless claim, one I hope was not replicated in the recent (and, to me, pointless)† miniseries Fosse and Verdon. Alas, it probably was.

Similarly, there are things in The Big Goodbye which, even when staring its author in the face, are missed. After describing the corrupt origins of Los Angeles in some detail, the author compliments the screenwriter Robert Towne on the authentic “noir” sound of the character he named “Hollis Mulwray” and seems not to know that it was simply a variation on that of William Mulholland, on whom the slightly more benign Mulwray was based. (There is also, Mr. Wasson, a rather well-known Drive in Los Angeles which still bears Mulholland’s name. Or don’t you know that either?) I am also a little dismayed by the book’s very title. Wasson may have thought he was getting at the sound or the style of Raymond Chandler and Howard Hawks, but is he unaware that “The Big Goodbye” is the name of a Peabody Award-winning, 1940s film noir time-travel episode by Tracy Tormé of Star Trek: The Next Generation, similarly titled to evoke The Big Sleep? Apparently not. I have almost no interest in Star Trek in any of its iterations, but even I knew about this.

Additionally, while briefly describing Barrie Chase, Towne’s first great love, Wasson refers to her as being in the chorus of some movie musicals. He seems to have no idea how famous Chase later became, or why. Wasson is too young, of course, to have seen Chase with Fred Astaire in his three NBC television specials (1959, 1960 and 1968) but so, except for the last one, am I. My relative youth, however, does not preclude my being aware that Chase was Astaire’s last great dancing partner, or from having seen extended clips from those shows, in which Barrie Chase proved that she was every bit as good partnering Fred as Ginger Rogers, Rita Hayworth or Cyd Charisse, and in some ways (her sly wit, her superb technique and her striking elegance) even better.‡

What, moreover, are we to make of that subtitle? That “Hollywood” ended in the 1980s? What Wasson means (and readers of this blog will know we entirely agree) is that the personal filmmaking that marked the 1970s as the last great era in American movie history ended after the success of Jaws made projects like Chinatown nearly impossible. But the industry hardly shuttered in 1975. (And no, I don’t think I’m being pedantic; Hollywood has never been healthier, financially, than it is today. It has also never been less healthy, artistically and creatively.) Further, Wasson sniffs at Jaws as if it is ordure only slightly redeemed by being entertaining ordure, when he should instead reserve his opprobrium for the way the picture’s over-saturation marketing replaced the traditional ability of movies to build their audiences over time. While my love for Jaws is not definitive — de gustibus, baby — I hardly think the picture is in the same category as Top Gun. Wasson scorns that one too, and rightfully, but doesn’t seem to comprehend why it got made: It was the ’80s, and Reagan was president. It was perfect, anodyne, America-made-great-again (and that was his slogan long before it was Trump’s) pabulum for people who can’t handle, and don’t want, anything stronger at the movies than a two-hour commercial advertisement for United States military hegemony.

One of the most demoralizing movie books of the last quarter century is also one Wasson’s publisher is eager to compare his to and to which, alas, bears it. (So did Fosse.) Peter Biskind’s sordid Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (Simon & Schuster, 1998) pretended to being a paean to the innovators of the 1970s but was far more interested in tearing them down and trashing their reputations. The book was little more than a collection of ground axes and (alleged) bad behavior, a new edition of Hollywood Babylon, updated. There is nothing (I repeat: Nothing) in the book of wisdom, of delight at quality achieved, of love for the medium or appreciation of the movies Altman, Ashby, Polanski, Pakula, DePalma, Spielberg, Bogdanovich, Coppola, Scorsese, Penn and Fosse and their collaborators carved out of a dying studio structure; of how extraordinary actors like Fonda, Brando, Burstyn, Streisand, Beatty, Pacino, Hackman, Dunaway, Scheider, Bridges, Duvall (Robert and Shelley) and — supremely — Nicholson were in them; or about how beautifully the William Goldmans, Alan Sharpes, Alvin Sargents, Joan Tewkesburys, Willard Huycks, Gloria Katzes, Buck Henrys, Paddy Chayefskys, Robert Townes and Edward Taylors crafted the screenplays for the movies we now acknowledge (and which were, indeed, acknowledged then) as the reasons the decade constituted a classic period for American movies, one it seems increasingly obvious we will never see the like of again.

(I see the wheels turning in your head. Edward Who? Read on.)

Robert Towne accepting his solo Oscar® for Chinatown. He looks spooked, as if someone has just asked him who Edward Taylor is.

After slamming Peter Biskind for manufacturing an entire book out of gossip and bad press I am loath to put it this way; however, what is most memorable about The Big Goodbye is what’s most shocking about it. I refer not to the description of Roman Polanki’s indefensible statutory rape of a 13-year-old girl but to the revelation that no script the vaunted Robert Towne ever worked on, from his earliest days as a screenwriter to the death of his alleged best friend, was written without the direct, and daily, input of that friend, the heretofore unknown Edward Taylor… and that includes the screenplays he famously doctored. Wasson himself, in an interview about the book, says he’s still stunned by what he discovered about Towne and Taylor’s decades-long collaboration, for which Taylor was mildly compensated fiscally and seemed not to care that another man took credit for every script he ever co-wrote, or conferred on.

This revelation is only slightly less astounding than the details of Towne’s deliberate cocaine addiction, the wreckage it made of his life, his marriage, his friendships and his ability to function creatively — among other things, it destroyed the first attempt at filming The Two Jakes, costing Paramount millions and alienating both Robert Evans and Towne’s close friend Nicholson — and his staggeringly hypocritical behavior toward Julie Payne, his ex-wife and the mother of his child, whom he with the aid of a family retainer tarred in court with his own sins, and successfully. One almost feels the urge to tip one’s hat to Towne for, if nothing else, sheer physical endurance. To build one’s entire career on a lie is nothing new. To maintain that lie for decades requires stamina at the very least. The late Harlan Ellison once wrote a variation on the old “Cobbler and the Elves” story (“Working with the Little People,” collected in Strange Wine) about a played-out writer who maintains a career that should have ended long before (o irony!) due solely to the beneficent assistance of leprechauns. I wonder if even they could have kept their mouths shut as long as Edward Taylor did.

Although I could have done without Wasson’s all too frequent forays into prose poetry (they’re either portentous, pretentious or both) one area in which he does excel is in conjuring the aura of the late ’60s, and especially in illuminating just how horrid Hollywood, and the American press, were toward Polanski after his wife and unborn son were sadistically slaughtered by members of the Manson Family. In the eyes of many, it seemed as if, merely having made Repulsion, Knife in the Water and Rosemary’s Baby, Polanski somehow willed what happened to Sharon Tate — as if he brought it on himself. Of his childhood in Poland, reputed to have been a model for Jerzy Kosinski’s novel The Painted Bird (another item Wasson never mentions) and the loss of his mother and sister to the Nazi demon the jackals of 1969 neither knew, nor cared. At a moment of numbing, horrendous grief over an insupportable act of violence that nearly leeched his sanity, Polanski became an outcast, the stench of his wife’s murder somehow clinging to him. By such logic one supposes there are those who think Stephen King asked to be plowed into by a minivan.§

Although The Big Goodbye contains some practical information on how Chinatown was filmed, there isn’t enough; it isn’t a “making of” book (more’s the pity) and is often skimpy on details. Worse, it trots out the reliable, yawn-inducing old tropes (“Faye Dunaway was a bitch” is the most obvious) without anything approaching even-handedness. If Wasson had reached out to Dunaway and been rebuffed, that would be worth knowing. Alas, we don’t know, and her own book (Waiting for Gatsby) doesn’t seem to have been consulted by the author. Wasson also dismisses Nicholson’s post-Chinatown work out of hand, as if, amidst the tripe and the big payday items such as Batman, he never after 1974 made anything else of value, or gave another great performance. And even after limning the Nicholson/John Huston relationship, reporting on Jack’s admiration for the old director and his troubled romance with Huston’s daughter Anjelica, Wasson never even mentions Prizzi’s Honor, lamenting instead that after the ’70s Nicholson no longer played roles that challenged him. A dim-brained, thickly-accented New York mob assassin wasn’t a stretch? (Cut it out, Ross! You’re hashing my narrative buzz!) Well, poor Warren Beatty barely merits a mention here, not even an expression of admiration for his getting a studio run by Gulf & Western to finance and distribute Reds (in which Nicholson co-starred) his $30 million paean to a pair of American Communists.

And now, at last, we come to the reason for this review, to the gravamen of my argument against shoddy writing and to the grounds for my despairing of Wasson specifically, and the decline of American authorship generally.

Tucked into The Big Goodbye‘s account of Oscar Night 1975, and Wasson’s digression about Francis Coppola’s Best Director award for The Godfather, Part II is this, which comes at the informed reader with the force of a body-blow:

“But [Robert] Evans knew that the Academy, having previously awarded Cabaret Best Picture over The Godfather, would give Coppola his due this year.”

Cabaret did not win Best Picture. The Godfather did. How the former did upset the seeming surety of Coppola’s triumph was in the Academy voters giving the Best Director statuette in 1972 not to him, but to Fosse.¶

What removes the error cited above from the realm of the trivial — and there are few things in the world more trivial than the Academy Awards — is that the writer who made that howler… wrote a 600-page book on Bob Fosse.

Wasson didn’t even need the Internet. All he had to do was open his own goddamned book.

The only thing more distressing to me than Sam Wasson’s lazy work habits is the plethora of articles and reviews about his book which, in an increasingly clumsy fashion, are represented by headlines evoking the movie’s famous closing line. (“It’s Chinatown, Jake” and “Forget L.A., Jake” are two of the more brilliant examples.) Well, what can be expected when Wasson himself ignores perhaps the most relevant line of dialogue in Chinatown, one to which my headline alludes. It is here, in Gittes’ first confrontation with the genial monster played by Huston. (As you read this, remember that Noah Cross consistently mangles Jake’s surname as “Gits.”)

Jake Gittes: How much are you worth?

Noah Cross: I have no idea. How much do you want?

Jake: I just wanna know what you’re worth. More than 10 million?

Cross: Oh my, yes!

Jake: Why are you doing it? How much better can you eat? What could you buy that you can’t already afford?

Cross: The future, Mr. Gits! The future.

It is that very future for which, when I encounter such migraine-inducing imponderables as how a man can so little know his own previous subject, I tremble most.

*”The James Bond Theme” was Norman’s adaptation of a song (“Good Sign, Bad Sign”) he’d written the year before Dr No, for a planned stage musical, with Julian Moore, of A House for Mister Biswas.

†I don’t want to see any actors portraying other performers, particularly ones as well-known, and as reproduced, in performance and interview — or as unique and idiosyncratic — as Bob Fosse or Gwen Verdon. At best one gets a pale imitation of the genuine article, at worst a caterwauling travesty which, other than serving as Oscar-bait, has no value whatsoever. (Note, too, that the producers of Fosse and Verdon felt compelled, in this age of #MeToo, to insert Verdon’s name into the title of a series based on a book called Fosse.)

‡Chase was famous enough to be cast (as Dick Shawn’s mod dancing partner) among those dozens of other guest-stars in It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. She was also, memorably, the young woman brutalized by Robert Mitchum’s Max Cady in the 1962 Cape Fear, in some way too horrific to be mentioned, which made contemplating it even more horrendous.

§Tom O’Neill alleges, in his book Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA and the Secret History of the Sixties, that Polanski kept a cache of video tapes at the house which, among other things, depicted him raping his wife, and which the corrupt Los Angeles legal authorities knew of. I’m not disputing that in the slightest, nor that Polanski is in many ways a reprehensible human being. But, again, how is any of that an indication that Sharon Tate deserved, because she was married to him, to be stabbed repeatedly in her pregnant belly?

¶While Godfather purists, many of whom weren’t even born in 1973, still scream at this, Fosse’s direction of Cabaret deserved all the recognition it received. Acknowledging that in no way diminishes Coppola’s own splendid achievement. It was one of those years when you wish there had been a tie. But excessive bitching 50 years later merely points up how ludicrous award shows are.

Text copyright 2020 by Scott Ross