By Scott Ross

I first saw Rollercoaster at 16, at an especially rotten little shopping center duplex cinema in Raleigh, North Carolina; it had earlier been a single-screen theatre until some genius decided to split it in half, around 1974 or ’75 — I remember seeing Jaws there — and the place was like two small coffins separated by what seemed like strips of plywood wedged between the auditoriums. I don’t recall what was playing next door in ’77, except that I remember seeing whatever that was the week before. The theater held 99-cent screenings every Tuesday evening; whatever the other movie may have been (the atrocious Fire Sale, possibly) I recall, while watching it, the sound and feel of Rollercoaster’s utterly gratuitous Sensurround process bleeding through the walls and vibrating up from the floor, which is precisely as annoying as you might imagine.

It was that very, expendable, addition that had kept me from Rollercoaster initially. One of Universal’s periodic attempts at manufacturing a fad, Sensurround debuted, appropriately, with Earthquake in 1974, sticking up its noisy, bombastic head at periodic (and wholly doomed) intervals until mercifully giving up the ghost for good in 1978. I had, however, a high school friend who was pretty much game for anything at the cost of only a buck, so we went.

My friend wasn’t particularly impressed with Rollercoaster, but I was — despite its being, essentially, a made-for-television movie decorated with widescreen, a few mild profanities and that ubiquitous sound-and-shake process. Its pedigree was, in fact, very television for the time: The movie’s canny screenplay was by William Link and his (now late) writing partner Richard Levinson.

Richard Levinson (left) and William Link.

The team responsible, among other things, for Columbo, Levinson and Link had also written and produced the now hopelessly dated but, in 1972, exceptionally brave teevee movie That Certain Summer starring Hal Holbrook as a divorced father, a young Martin Sheen as his lover, and Scott Jacoby as Holbrook’s alienated son. In later years I would especially admire Levinson and Link’s neat cat-and-mouse thriller Murder by Natural Causes, their evocation of 1957 Little Rock (Crisis at Central High) and their marvelously convoluted three-hander Guilty Conscience with the drop-dead triple-header cast of Anthony Hopkins, Swoosie Kurtz and the divine Blythe Danner.

Rollercoaster was another exercise in L & L’s patented games-playing: A chilly young man (Timothy Bottoms) sets off a series of bombs at large amusement parks around the country, the escalations gradually revealing themselves as blackmail — so perfect a terrorism plot I’m surprised no one in these post-PATRIOT Act times has re-made the movie… or, if they work for the FBI, have tried to re-enact it.

Matching wits with this unknown (and largely unseen) antagonist is the engaging George Segal as Harry Calder, a California ride inspector. Naturally, once Harry deduces what the boyish sociopath is up to, no one in charge of the investigation takes him seriously until — also naturally — The Young Man (as Bottoms is billed) strikes again. From there on, Rollercoaster focuses on Harry, as The Young Man puts him through a series of seemingly pointless maneuvers though Virginia’s King’s Dominion park (and, later, the Six Flags Magic Mountain in California) as the Fibbies pursue them both.

It is finally Harry, the Young Man’s cats-paw, alone and feeling increasingly extraneous (and foolish) who is able — once the psychopath’s original plans are frustrated and he resorts to an improvised act of vengeance — to suss out Bottoms’ modus operandi.

Put that baldly, you may well wonder what the attraction was, and why I went back to Rollercoaster a second time, Sensurround and all. Gimmicks aside, the movie has a fascination even after you’ve seen how it comes out. It certainly wasn’t due to any great job of filmmaking: The director, James Goldstone, came from television and, after, pretty much stayed there. Rollercoaster was Universal’s “event” movie that summer, the one the studio was sure was going to be the big hit of 1977. (They, along with everyone else, just didn’t reckon on something called Star Wars.)

Goldstone directing Widmark on the set.

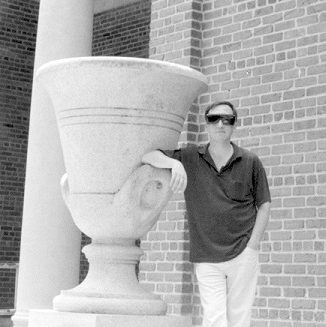

Much of the spell Rollercoaster’s cast on me was due to L & L’s smart, wry screenplay.* A part of it was undoubtedly my then-nascent sexuality; Timothy Bottoms was a dreamboat.

Part of that effect surely sprang from David M. Walsh’s expansive, and occasionally effectively vertiginous, widescreen cinematography: The otherwise fine 2:35 DVD presentation can’t come close to approximating the sensations you got in the theatre as Walsh’s camera took you through the rides themselves and, in one especially hair-raising moment (later appropriated by Stanley Kubrick for The Shining) seemingly off the tracks and away, into the sky. An additional a large portion of my admiration was Lalo Schifrin’s superb score; I played the soundtrack LP a lot that summer. It’s still a favorite.

While Richard Widmark makes the most of his role as a bellicose special agent, much of the fine supporting cast is underutilized: Henry Fonda as Segal’s sour boss, Harry Guardino as a local police inspector, and Susan Strasberg as Segal’s inamorata. You do get to see an adolescence Helen Hunt, Jodie Foster’s main competition in the “bright pubescent” sweepstakes, as the divorced Harry’s daughter, if that’s any compensation. (You may wonder, however, from a dramaturgical point of view, exactly why Strasberg and Hunt show up, against Harry’s wishes, at Magic Mountain in the final reel; they’re not put in peril, which is what you expect, and while the willingness of the screenwriters to thwart that cliché is admirable, it makes the pair’s unexpected appearance — especially as Harry convinces them to leave the park as soon as he sees them — feel entirely extraneous.)

Wait… is that Jodie Foster?

If you are, as I am, a life-long fan of George Segal, nearly any excuse to watch him at work is sufficient. Segal is one of those rare actors, like Elliott Gould in the same period, who without seeming to do much of anything radiates likability, and quiet intelligence. And since Harry Calder is in nearly every scene following the terrifying accident in the opening reel, he becomes the audience’s surrogate; his confusion is ours, his rages and frustrations our own as well.

I suspect my positive response, then, was due to a blend of elements, not the least of which was the wholly unexpected surprise of being treated, even at 16 and especially in the summer, like someone with a mind during the unfolding of what was, essentially, a slick studio programmer.

Or maybe you just had to be there.

________________________________

*Tommy Cook and Sanford Sheldon are credited with, respectively, “story” and “screen story.” One smells a whiff of Writer’s Guild arbitration threat there.

Post-Script, January 2021

Some of the reader comments below, and my replies to them, may be puzzling to a new reader of this review. They were occasioned by my previous reference above, since deleted, to Timothy Bottoms’ having made homophobic statements in the past. One (by Bob, who below shares some of his experiences working on Rollercoaster) more than questioned my assertion, based on his observations of and interactions with Bottoms during filming. This set me to wondering if I had confused Timothy Bottoms with another actor. An online search yielded exactly one line, in comments on a gossip site, in favor of the notion that Bottoms was anti-gay, and the writer cited nothing to substantiate his claim.

I then went where I should have gone when I wrote this piece seven years ago: To my personal library. There, in Leigh W. Rutledge’s 1988 book Unnatural Quotations (page 20) was my answer. The actor in question was Joseph Bottoms, one of Timothy’s younger brothers. Rutledge quotes Joseph to wit:

I don’t hate gays, but I believe they’re awfully unfulfilled human beings. I really think homosexuality is a dead-end street. It’s self-adulation. It’s masturbation… I feel sorry for them because it’s unnatural.

Interestingly, Joseph later appeared on Broadway in the late gay playwright Lanford Wilson’s wonderful comic drama — and my favorite American play — The Fifth of July, the leading character in which (and the role Bottoms played, after Christopher Reeve, Richard Thomas, Michael O’Keefe and Joseph’s brother Timothy had done so) is a disabled gay Vietnam veteran. Three years later he was a gay football player in Celebrity, a television miniseries. Most interestingly, he is the only one of the Bottoms boys (Timothy, Sam and Ben), all of them actors and all beautiful, to be photographed nude for the (very) gay entertainment magazine After Dark, in 1978.

It grieves me to think I have maligned an actor I admire, and contributed to spreading misinformation online, especially when the answer was no further away than my bookcase.

Thank you, Bob, for sending me where I should have gone before.

Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa!

Text copyright 2013 by Scott Ross