By Scott Ross

This utterly charming romantic comedy, one of the most completely enjoyable I’ve ever seen, was one of several movies of its time I missed getting to at the theaters, in part because of reduced fiscal circumstances, in part because they often didn’t stick around longer than a week (and just as often never showed up at the cheap second-run houses)* and in equal part due to my reading or otherwise heeding the opinions of critics whose interpretive intelligence I later learned to question if I wished to protect my own, genuine responses, unblemished by allowing what others whose minds I did not respect wrote or said to become implanted in mine. At that time, I used reviews in newspapers and magazines largely as consumer-guides, and if a picture like All Night Long got enough opprobrium there I could cross it off my shopping list. This seems both the most common use of such reviews and the best argument against them.

The critical response to what, if you are open to its quirky characters and gentle European rhythms, is as bright and likable as the great screwball farces of the 1930s, was dismal, and dismaying. Take Vincent Canby in The New York Times: “[H]ardly a bit of it is believable or coherent. Yet All Night Long is never really boring, if only because one can’t believe the high quality of the utter confusion that occupies the screen… Everything in the movie is at sixes and sevens… a collection of random inspirations and ideas with no center of gravity. They appear, hang around a while and just drift away. It doesn’t leave one bored as much as baffled.” Or Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times: “Surely it wasn’t Streisand’s idea to play her character as a quiet, vacant-minded nonentity. Here’s one of the most powerful personalities in movie history, and she doesn’t have a single scene where she lets loose. She’s almost intimidated by the clothes she wears… [All Night Long] could have developed into a fascinating portrait of all-night society, but it doesn’t. It assigns a few weirdos to march through the store and do their thing, but they don’t feel real, they feel like actors. The story never approaches the rhythms of life… the director keeps losing the pace. Scenes begin with the promise of fireworks and end with the characters at a loss for words. You also know a movie’s in trouble when it has the heroine ride a motor scooter just to make her seem like more of a character… [T]he movie never really gets going. It’s got all the ingredients, but it feels a million miles from life.”

I don’t know what movie Canby and Ebert saw, because what’s on the screen is, in its small, unassuming way, pretty much perfect. I strongly suspect that the people who carped at All Night Long knew too much about the circumstances of its making, as Canby admitted in his review. And while I know I risk sullying your possible enjoyment of the picture by rehearsing them here, the details seem relevant.

According to William Goldman in his influential book Adventures in the Screen Trade, the basic germ of what became All Night Long originated with its director, Jean-Claude Tramont, who thought it might be interesting to take a look at people who work at night. Universal Pictures assigned the notion to the gifted screenwriter W.D. Richter, who came up with a honey of a script concerning a pharmacy chain executive discontented at work and at home, his demotion to managing a 24-hour urban drug supermarket, his desire to devote time to his inventions, and the married kook he becomes involved with after getting her to call off an affair with his 18-year-old son. Gene Hackman read it and was so avid to play the lead he offered to defer part of his salary in exchange for a profit percentage. The studio, penny wise and pound foolish, refused, so the whole of Hackman’s $1.5 million salary got added to the picture’s modest ($3 million) budget.

So far, so Hollywood normal. The movie begins shooting, with the criminally underrated Lisa Eichorn in the secondary role of Cheryl, the kook. Three weeks in, enter Sue Mengers, one-time super-agent, wife to Tramont and whose primary client is one Barbra Streisand. Suddenly Eichorn is out and Streisand in. And while to her credit she did not ask for her role to be enlarged, Streisand (or Mengers) did demand — and receive — a then-record $4.5 million, further inflating the small original budget to what ended up, with print, advertising and other distribution costs, closer to $20 million. And if those figures seem miniscule today, remember that we are talking about 1980 dollars, worth roughly three-and-a-third times what the same dollar represents in 2021.†

Even with Streisand on the marquee, the picture died at the box office. Had Mengers not bloated the budget (Merci, mon amour!) All Night Long, which took in just $4.45 million, might with video and television sales have eventually (if barely) broken even. If there is any cosmic justice to be had, it lay in Streisand’s subsequent dumping of Mengers as her agent, a move largely related to the movie bombing. But that didn’t help the picture any.

One of the more interesting aspects of Ebert’s review was his determination that All Night Long didn’t work because Streisand didn’t dominate it. Yet her steamroller persona, evident in nearly every movie she had made to that point, is the main reason a lot of people have never warmed to her and why even those of us who love her as a performer sometimes find her unbearable. If moviegoers who felt antipathy toward her had been given a chance to see her as a sweet, lost soul with dreams she can’t attain — if a few prominent critics with large enough audiences had made them aware of the picture, and how good she was in it — I suspect they might have finally found a Streisand movie they could like.

Except it isn’t a Streisand movie, and that, for most critics, was why it didn’t work. Reviewers say they want more variety from movies, and from actors, but when they’re confronted with true originality they are usually hostile to it, and when a star like Streisand tries something new they slam her for it. (She was equally subdued, and excellent, in Up the Sandbox in 1972 and the critics carped about, and movie audiences stayed away from that one as well.) Even Pauline Kael, who was unique in enjoying All Night Long, and a longtime Streisand admirer, felt the actress was miscast, largely because she didn’t think Cheryl was a character Streisand drew out of her own persona.‡ Funny — I thought creating fresh characterizations is what actors do.

Although there is such a thing as consensus, neither my response to a given movie nor yours is definitive. This seems to be especially true of comedy. Chaplin is generally recognized as a genius, but there are avid movie fans who are cool to him. Orson Welles said he understood that Chaplin was funny because everyone else thought he was, but that he was incapable of laughing at him (although I strongly suspect his statement was colored by having to sue Chaplin over credit for Monsieur Verdoux) and I know one writer who said of Blake Edwards, a favorite in my home, that his pictures “leave a trail of slime” behind them. Still, even if you don’t care for a comedy on the basis of its content or presentation, even if you think it witless or plain stupid, you know whether its logic holds or not. I personally loathe It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, about as mean-spirited, self-righteous and unfunny a comedy as anyone has ever made in America, and a near-complete waste of the dozens of great comedians who appeared in it. Yet never once have I suggested it doesn’t make sense.

Whatever Canby or Ebert thought of All Night Long, I don’t see how either could claim that the movie is not “coherent.” It has a point of view, off-kilter though it may seem to some, and its characters, and their actions, however unusual (and who watches movies or goes to theatre performances to see depictions of normalcy?) are, within their own individual lights, perfectly logical. As to Canby’s weird complaint that the incidents in the picture “have no center of gravity,” I have no more idea what the means than I do Ebert’s criticism that the movie’s story “never approaches the rhythms of life.” What are these “rhythms of life” he’s whingeing about? And are the “rhythms” of The Awful Truth those of life as anyone knows it, or knew it in 1937 when audiences first started roaring with laughter at it? Well, Ebert always did use selective criteria. (Talk about a lack of coherence.) But why the hell is Cheryl’s riding a scooter rather than, say, driving a Honda Accord or a Mercedes-Benz, a desperate attempt by the filmmakers to “make her seem like more of a character”? Did Ebert think only a kook would ride a scooter?

All Night Long isn’t necessarily the funniest comedy you’ll ever see, yet from the opening moments, before a single character is glimpsed and voice-over dialogue is met by inspired sight gag I laughed often, and smiled consistently. When an opening gambit works as well as that one (and I won’t spoil it for you) you can relax; you’re in the hands of people who know what they’re doing, and how to do it. Richter, who wrote the enjoyable shaggy dog story Slither (1973), the witty 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers and one of the two scripts incorporated into Nickelodeon (1976) has an obvious affection for the square pegs trying to fit into the round holes of American life, or who have given up trying to fit in and no longer care what others think of them. On one end of this spectrum is Cheryl, the good-natured disappointed singer/songwriter mired in a loveless marriage with a macho creep (Kevin Dobson), who makes up what she thinks are creative recipes from canned goods and takes in lovers, like young Freddie (Dennis Quaid) when her fireman husband, who works nights, is out of the house. On the other is Freddie’s would-be inventor father George (Hackman) who loathes his job and his bosses and is likewise trapped in a loveless marriage with a status-conscious hausfrau (Diane Ladd) with whom he seems to have nothing in common. It’s only when George, who objects to his son being involved with a married woman, intervenes to dissuade Cheryl from continuing the affair that the two become attracted to and enmeshed with each other.

All of this suggests the set-up for a ribald sex-farce, but All Night Long is a gentle comedy about misfits, two of whom defy the odds by finding each other. There is one scene that holds the contours of farce, when Freddie comes to see Cheryl while George is (innocently) in her bedroom and she tries to get rid of the boy before he discovers his father on the premises. The sequence isn’t played out frenetically, however, or with that smirking aspect that so often turns farce into the acceptably dirty — smut for people who hate pornography.

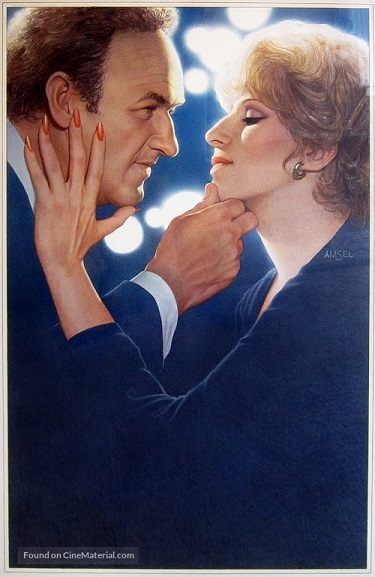

What really does seem obscene was Universal’s poster with its suggestive Drew Struzan artwork that simultaneously offended Streisand and caused the preview audience to expect a brassy Barbra Streisand comedy à la The Main Event, taking a sweet moment in a firehouse near the end of the movie and making it appear to anyone who doesn’t know the scene that Cheryl is some sort of pole-dancer sliding into the arms of three different lovers. What movie did Struzan think he was illustrating? Porky’s?

As a director, Jean-Claude Tramont matches Richter’s tone, which is at once generous of spirit toward the people in the picture and at the same time lightly satirical about them. His sense of timing is distinctly European, and I wonder if some of the negative critical reaction to the picture was due to the characters speaking English; if George and Cheryl had been French, would some of the same people who carped about the movie not instead have rhapsodized over it? Tramont was hampered by the studio-bound look of some of it, particularly in the exterior night scenes, although I can imagine the same auteurist types who go into ecstasies over the patently phony matte painting of the harbor in the Hitchcock-directed Marnie would probably have hailed Tramont as a genius had they seen All Night Long. I would say in this case, however, that if you succumb to the picture’s charms you don’t mind the artifice, especially when Richter’s dialogue is zipping along, as when the bellhop in the hotel into which George moves when he leaves his home apologizes for the condition of his room by shrugging, ”The maid’s sick. Spinal meningitis.”

It’s the unexpected in All Night Long that keeps you smiling and the action from foundering on the shoals of cliché. The movie almost never goes where you expect it to; every time you think you know what’s about to happen, or how a character will react to it, the picture surprises you — another reason I suspect the likes of Canby and Ebert were confused by it; to foil mundane expectations upsets mediocre minds. Certainly the reaction to Streisand’s performance seems wedded to expecting the usual, and not getting it. Because Cheryl is soft where Streisand is often hard and pliant where the actress tends to be unyielding, these reviewers found her lacking, and miscast, “endearingly so,” according to Leonard Maltin, who gave the picture a 3 ½ star rating anyway. Cheryl is seductive without pushing, and Streisand employs a mincing walk that, coupled with her high skirts, short blonde cut and penchant for lavender and mauve (including on the walls of her home; the paint almost seems to have been picked to match her outfits and her eyeliner) make you understand why men find her irresistible.§ Cheryl isn’t as funny as some of Streisand’s best characters (Fanny Brice, Judy Maxwell in What’s Up, Doc?) and isn’t meant to be. Even when she’s sitting at her piano singing a song she’s written and both the song and her voice are just slightly off, you don’t laugh at her. You may smile, both at her earnestness and at the greatest pop singer of her time choosing to perform badly, but Cheryl is too likable a figure to make fun of.

It’s impossible to overpraise Hackman’s work in All Night Long. He’s always been a wonderful comedian, although until Young Frankenstein few people seemed to recognize how witty he could be, and how engaging. His George is, despite his discontent, easygoing and open; he not only rolls with the punches but seems to find the battle itself more amusing than frustrating. Yet he’s no pushover, as the opening scene makes clear, as well as the sequence in which he visits Cheryl and her dour, firefighting husband in their backyard. He knows he’s putting her in a bind but he’s too worked up to be kinder, and he won’t take her resignation and fear lying down. His belief in her worth gives her the courage she needs to make the change she wants. Hackman was never a conventional leading man, and he’s not handsome enough to cut the sort of figure the general run of movie romance requires. The former was always his strength as an actor and the latter illustrates how shallow the genre tends to be, and why All Night Long is such a refreshing change.

Although Diane Ladd as George’s materialistic wife Helen has relatively little to do, she limns her character so completely from her first scene that nothing more is really needed. As Bobby, Cheryl’s unappreciative husband, the dependable Kevin Dobson ably treads a fine line between boorish and brutal; although we don’t know that he’s ever hit his wife, the threat is there, unspoken but never far from the surface. Yet he’s easily dispensed with: In one scene late in the picture he drives with Freddie to the Italian restaurant where George, who’s walked out on the all-night drug emporium, is employed as a singing waiter. And here’s what I mean when I say that All Night Long doesn’t go where you expect it to. Any other movie, even a romantic comedy, would have at that point have devolved into fisticuffs at worst or a screaming match at best. In this movie, the staff diffuses Bobby’s confrontation by bursting into song (which Freddie joins in) and, en masse, escorts him from the premises. It’s a delightful reversal of expectation, and exactly what the viewer most wants to see at that moment even if he or she doesn’t know that until it happens.

He was too old for Freddie (the boy is 18 and the actor was closer to 30) but Dennis Quaid is such an appealing, uncomplicated presence he captures the essence of an aimless teenager besotted by an older woman, infuriated when he thinks his father is moving in on her, petty enough to encourage Bobby’s confronting George and yet open to seeing the fun in Bobby’s failure. (Freddie’s forgiving George without recourse to any soupy, emotional father-son reconciliation is another point in the movie’s favor.) William Daniels has an amusing small role as an exceedingly well-heeled divorce attorney; he has a perfect moment late in the movie when he realizes he has no defense and has just blown a heavy settlement in favor of Helen. Richard Stahl gets a nice bit as a pharmacist, the Amazonian Faith Minton a hilarious scene as a would-be robber, and Hamilton Camp a good gag as one of the nuts who frequents the pharmacy. Irene Tedrow is gruff and wonderfully dry as the landlady of a loft George rents for his workshop and Vernée Watson lends marvelous presence as one of George’s cashiers.

Although Richard Hazard and Ira Newborn are credited with the picture’s music, there is little evidence of their work. The most prominent items in the musical score are a diverting little theme for Cheryl by Dave Grusin and a pair of charming pieces from two of Charles Chaplin’s masterpieces. Tramont asked Georges Delerue to write an arrangement of José Padilla’s “La Violetera,” which Chaplin featured in City Lights and which not only serves as a poignant love theme but also comments without words on Cheryl’s love of violet shades. Delerue created a second Chaplin arrangement, this time of the Léo Daniderff song “Je cherche après Titine,” which Chaplin performs a nonsense version of in Modern Times. (You can hear it as the underscore in the movie’s trailer.)

Invoking Chaplin in a modern comedy is a dangerous move. It risks your movie being damned by comparison, and few either could get away with it, or should. All Night Long in no way consciously evokes Charlie, but somehow the musical analogy seems apt.

*My “lost” pictures for that year, about half of which I’ve since caught up with, include Cutter’s Way, The Chosen, Raggedy Man, Only When I Laugh, Blow-Out, Cattle Annie and Little Britches, The Incredible Shrinking Woman, Heartbeeps, Dragonslayer, Whose Life is it Anyway?, Buddy Buddy, Pennies from Heaven and They All Laughed. I wanted to go to many more movies than my low-paying job at the time permitted; now, since 1981 appears to have been, as far as American cinema is concerned, the last year of the 1970s, I’m even sorrier I missed so many good ones on the big screen. (For the record, the better non-genre movies of that year I did manage to catch included Absence of Malice, Das Boot, My Dinner with Andre, Prince of the City, Quest for Fire, Reds, S.O.B., True Confessions and Wolfen.)

†By way of perspective, when Brando demanded $3.7 million for his extended cameo in the 1978 Superman, the payout was considered obscene; Woody Allen routinely made entire movies for that price, or less.

‡I should add that, while Goldman praised Streisand for wanting to play Cheryl as written, Brian Kellow in his book on Sue Mengers says that she made requests for rewrites which went unheeded. Since Kael usually had her ear to the Hollywood ground, perhaps she’d heard that.

§In a nod to Cheryl’s taste. the witty French title for All Night Long was La Vie en Mauve.

Text copyright 2021 by Scott Ross