By Scott Ross

Reviewing the Jules Dassin-directed Up Tight at the time of its 1969 release, Roger Ebert complained that adapting The Informer to a contemporary black revolutionary context was a graft that didn’t take, arguing that Liam O’Flaherty’s novel did not center on IRA activities but rather on the guilt of the protagonist. That, it seems to me, was too literal a reading for so freewheeling a project as this. Think of Up Tight less as a “remake” or even as a strict transliteration of The Informer and more as a variation on it, and you come closer, I believe, to the spirit of the thing.

O’Flaherty’s book was written in 1925 but set in 1922, following the Irish Civil War; by placing Up Tight in the black ghettos of Cleveland four days after the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr., the filmmakers were getting at something very similar, in expressive terms, to the raw emotions the Irish experienced following partition. (The picture begins with footage of the civil rights leader’s Atlanta funeral.) King’s symbolism within black America, pro or con, cannot be understated, any less than the grief and frustration and rage that exploded after his murder. A killing, moreover, which was carried out, by FBI agents, under the direct orders of J. Edgar Hoover. Scoffers ask why, with Dr. King’s effectiveness as a public figure largely blunted by passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965, the Establishment would bother. If we may dismiss as ludicrous the idea that a bill solves all the social ills it was meant to address — and we have only to look at the state of things now to do so with impunity — we must also ask: What was the focus of King’s activism when he was assassinated? Poverty, and war; specifically, the war in Vietnam. The powers directing the official powers may tolerate social agitation on matters of race, or sex, or sexuality, but when you question the very structures that hold the working and underclass in poverty and those dictating what the historian Charles Beard called America’s “perpetual war for perpetual peace,” then something must be done about you… and something duly was. That this did not occur to the makers of Up Tight in 1968 is not a grievous fault; the picture rides on so much that was in the air at the time it was made that it may surely be forgiven for missing a philosophical or historical nuance here or there.

Not that Up Tight is necessarily subtle. Its revolutionaries’ dialogue in particular has a blunt feel that places as much distance between us and the picture now, in the third decade of the 2qst century, as lay between the 1935 John Ford/Dudley Nichols adaptation, and Up Tight itself in the late 1960s. Indeed, if anything the latter feel even further in the past. The movie’s concerns, however, were very much in the present when it was written, filmed and released: Race riots broke out in 1964, accelerated after 1966, and hit special prominence in 1968, in Watts, with more to come in the early 1970s. It should be remembered as well that weapons manufacturers, the police and the NRA only got concerned with the enforcement of strict gun control when the Black Panthers talked of buying arms, or went out of doors with them. There were many then who firmly believed a racial war was not merely possible in America and elsewhere in the West, but inevitable. Wither, without those endlessly articulated white fears (and the manipulations of the sick geniuses behind MK-Ultra) a Charlie Manson?

For my own part, I find the adaptation of O’Flaherty, by the movies star Julian Mayfield, its featured actress Ruby Dee, and Dassin himself, not only apt but cunning. Revolution was in the air then (as it damn well should be now, and shows few signs of being, save on the radical left, liberals being content to put on pink caps, denounce a monstrous egotist, snipe at that very left and call themselves — presumably after watching The Force Awakens once too often — the “Resistance.”) And, pace Roger Ebert, revolutionary activities are very much a part of the novel, or why does Flaherty’s anti-hero Gyppo Nolan betray his friend Frankie Nolan in the first place? Gyppo is throw out of the IRA for his inability to murder a Black and Tan as ordered, just as Up Tight‘s protagonist Tank Williams (Mayfield) is ejected from his revolutionary cell for his failure to assist in a robbery of arms that ends with the killing of a white security guard (and the legal implication of Tank’s best friend.)

Betrayal, as a dramatic subject, requires no civil war or even its possibility, although it is in a political sense that it is perhaps most easily grasped. The wages do seem to fluctuate, however: 30 pieces of silver in the age of Judas Iscariot became 20 pounds in 1922; by the time of Up Tight they were a thousand dollars. Today they hover around the eight-thousand-dollar mark — as cheap for the buyer as ever.

The amount hardly matters, of course; the sense of personal guilt in all three cases is where the drama lies. Like Frankie, Johnny Wells (Max Julien) is a fugitive, and Gyppo/Tank betrays his whereabouts to the police, leading directly to Johnny’s death. Tank is motivated in part by his love for Laurie (Ruby Dee) and his desire to get them both out of the poverty that has blighted their lives and the lives of her children, just as Gyppo commits his betrayal of Frankie to secure passage out of Ireland for himself and his love. And here the screenwriters of Up Tight up the ante, having the self-styled revolutionary leader B.G. (Raymond St. Jacques in an intelligent and coldly frightening performance) inform Tank that it was Johnny himself who recommended cutting his friend loose from what is called “the committee.” It is that sense of personal disloyalty (we are never certain whether Johnny made that statement or not, but we would not be remiss in doubting it) that pushes Tank over the ethical edge into lethal stool-pigeonry.

In addition to the sometimes less-than-felicitous dialogue, Up Tight is saddled with occasional directorial flourishes that go horrendously wrong — I’m thinking especially about the sequence in an over-lit arcade that is at once wildly theatrical and pictorially bizarre. A group of well-heeled white liberals surrounds an inebriated Tank, begging to know when the revolution will take place. (One woman in particular seems, in her grinning, pleading fashion, to want to be a victim; it’s a peculiarly direct parody of the extremes of then-current white liberal guilt of the Tom Wolfe gleefully critiqued in “Radical Chic.”) Tank is only too happy to spin an outrageous fantasy of dead telephone lines, beautiful black bank tellers informing their Caucasian customers there is no money, and NASA moon-shots aborted by revolutionaries, and this outré sequence is capped by Tank and his avid listeners being reflected in fun-house mirrors, which puts all too blunt a point on the monologue’s satirical edge: Theatre of the Absurd meets filmmaking of the avant-garde school, and it’s that marriage, not the mating of O’Flaherty and late-‘60s revolution, that falls hideously flat, and dates the movie most thoroughly.

Ebert in his contemporary review also faulted the sets by the redoubtable Alexandre Trauner, and the way they were shot, by the splendid Boris Kaufman, complaining of the artificiality of the settings (he compared them, dismissively, to Catfish Row) and the extensive night shooting which, to him, rendered these sequences as somehow phony in comparison with the day shots of Cleveland’s steel mills, garbage dumps and earthworks. The critic forgot, or did not notice, that Up Tight is a story told largely at night, and for good reasons — intentions an aficionado of film noir would instantly understand, as they would also comprehend why so much of the outside action takes place in the rain that turns gutters into neon-illuminated garbage streams. Trauner’s contributions seem to me especially felicitous, particularly in Laurie’s ramshackle home, the dilapidated boarding house the embittered Tank simmers in and in the oppressive project where Johnny’s mother lives and which becomes the scene of the movie’s violent confrontation between its inhabitants and the Cleveland police. It should also be noted how well Booker T. Jones’ spare musical score (and occasional song) serves the picture, and how effective the animated titles by John and Faith Hubley are — although, oddly, their depictions of Tank and Johnny as youngsters include a clear re-drafting of a famous 1960s Coca Cola ad featuring two boys lying on their backs and, defying all laws of liquid gravity, sipping from glass soda bottles turned straight down and which, if you know it, may cause you to wonder how they got away without that image sans corporate lawsuit.

One of the more interesting curlicues in the narrative is the presence of a gay pusher and police informer called, variously, Clarence or Daisy,* and played with amused panache by the marvelous Roscoe Lee Browne. The actor hardly underplays the character’s sexuality; indeed, when corrected by a white police commander over his use of the word “nigger” — the cop interjects, “Negro!” — a smiling Clarence replies, in those deliciously clipped tones of which Browne was a master, “No, sir. Nigger… stool pigeon… and faggot.” Yet, despite his elaborately “faggy” (yet somehow tasteful) digs and the presence late in the narrative of a somewhat hysterical young boyfriend, Browne’s Clarence is not nearly as contemptuously portrayed, or written, as any one of a phalanx of such figures cobbled up by white screenwriters, at the time and even much later. Clarence is no more despicable than Tank himself, or B.G., and considerably clearer in his conscience. Even when manhandled by B.G.’s enforcers, he displays no stereotypical, “feminine” cowardice. He stands up to it better than Tank does. One does wonder whether Browne had any input on the shaping of the role. An actor of exquisite dignity as well as diction — see The Liberation of L.B. Jones — he was himself gay, and I like to think he may have had some influence on the conception of Clarence who, while lounging about airily in a very brief bathrobe (and, incidentally, displaying a finely shaped pair of legs, as befits the former track star Browne was) never dips into caricature of the grotesque sort, all too often on display in movies of the period. If anything, he puts one of in mind of a slightly more flamboyant James Baldwin. (The blogger and critic Stephen Winter thinks the performance is a mesh of Baldwin and Jason Holliday, the black, gay hustler-subject of Shirley Clarke’s documentary A Portrait of Jason.) In any event, Browne’s is one of the very few such performances that, far from making you — as is usual — cringe, instead cause you to relish every moment he’s on the screen.

Up Tight teems with familiar names, although not all of them attach to specifically named characters, either in the end credits or at the usually fulsome imdb. The actress and trail-blazing black playwright Alice Childress — the very fine Trouble in Mind is hers — is listed, for example, but in what role? (I suspect she’s the smiling street preacher exhorting her flock in the rain, but never having seen her act I can’t be certain.) Michael Baseleon, as the now un-wanted white activist Teddy, has a fine scene arguing with St. Jacques, and Robert DoQui a very good sequence as a street speaker, with which he does wonders. Juanita Moore shows up all too briefly as Johnny’s understanding mother,† Dick Anthony Williams (billed as Richard) does splendidly by Corbin, whose essential empathy is subsumed by his revolutionary aims and Frank Silvera contributes a superb supporting performance as Kyle, the voice of moderation, overwhelmed by the manner in which non-violent resistance crumbles in the face of exploding impatience of the sort Langston Hughes foresaw in his poem “Harlem” (“Or does it explode?”) Max Julien gives his brief appearances as Johnny an openness of expression that veers believably from rage at Tank’s failure to abet the robbery to, later, a gentle sweetness of spirit that suggest less an idealized revolutionary icon than a fully rounded human being. Janet MacLachlan, alas, playing his sister (and B.G.’s wife) Jeannie, is given by the writers a single mode to express— sneering fury — and is unable to overcome its limitations. On the extreme other hand, St. Jacques, looking especially handsome in full beard, limns a disturbing portrait of the revolutionary whose otherwise admirable zeal has mutated into a rigid ideology that brooks no exceptions and that cuts him off from normal human emotions. Weakness is anathema to him, betrayal unforgivable. Comes the revolution, you feel, and B.G. will begin lining up for execution anyone he believes is less than 100% pure… or who has the almighty gall to disagree with him.

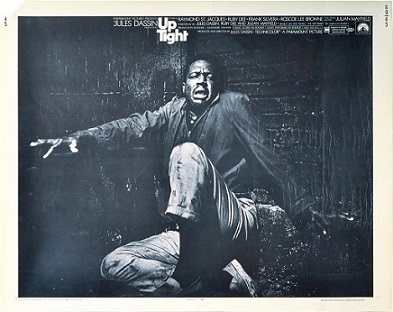

We expect Dee to deliver the goods, and she does, most notably in the late sequence in which Tank confesses to Laurie his involvement in Johnny’s violent death, after which she beats and scratches at him, flailing with her hands and fingers in a fury borne of equal parts grief and outrage. But Julian Mayfield, who was both a playwright and a novelist in addition to his work as an actor, is revelatory as Tank, infinitely more varied and moving than Victor McLaglen, who was given a 1935 Academy Award for his portrayal of Gyppo Nolan but who all too often in his screen roles became both brawling and bellicose, snarling one moment and brayingly riant the next. As Mayfield plays him, Tank is a man alienated by his times: Unprepared for the revolutionary fervor his best friend revels in, destroyed by his dismissal first from the only thing he loved without reservation (the steel mills) and later by the only substitutions for it he can find (the committee, and Johnny). As with Gyppo Nolan, Tank’s emotions run the gamut, but Mayfield is more controlled, even in extremis, than McLaglen (the depth of Tank’s pain can easily be read in Mayfield’s expressive eyes) and displays an actorly palette that suggests, poignantly, how fine a movie actor we lost when Up Tight failed at the box office. His own revolutionary concerns, and the usual fascistic surveillance of him by the FBI, may well have curtailed any such hopes all on their own; but that we will never know what he might have accomplished is, as it is always is in these cases, heartbreaking.

While Up Tight is, necessarily, dated, it — like the equally inflammatory The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973) — may prove prophetic, and unless we as a nation begin to address the appalling inequities of an increasingly Fascist system whose passive consent to atrocity and active murderousness toward its citizens has, since at least the 1980s, grown increasingly systemic — may prove prophetic. The dream can only be deferred for so long.

The explosion is overdue.

— December 2017

Post-script, 2024 Due to “improvements” since 2017 by the Word Press Happiness Boys, or whatever they call themselves, I have had to re-post this review just in order to reduce the size of the accompanying illustrations. As this meant deleting the earlier post, the comments therein by my friend Eliot M. Camarena, whose recommendation led to my seeing Up Tight, were also jettisoned. Since I not only find them relevant but wish I’d made them myself, I reproduce them here:

Eliot wrote, “Worth noting, it’s Jules Dassin’s only American film after the 1940s-1950s blacklist. A time like our own now…

“Ebert to the contrary, I found Alexendre Trauner’s sets so realistic that I did not notice them for the most part. Is that not a designer’s job? Especially pregnant with meaning: the set of a dilapidated bowling alley in which revolution gets planned. To me, it says: The time for games has passed.”

___________________________________________

*In a bizarre coincidence, one of my father’s brothers-in-law, whom no one would have considered in any way effeminate or “faggy,” was named Clarence… and his nick-name was “Daisy.”

†I’m reminded by the brevity of Moore’s role as Mrs. Wells of a remark made recently by, I think, Octavia Spencer, that winning an Oscar diminishes one’s career: Producers who might offer a part to you, she says, decline because they think, holding a statuette, you won’t deign to take it. Or, perhaps, having been close to holding one: Moore, nominated for Imitation of Life in 1959, kept working into her 80s but never again in a role as important, or as showy.

Copyright 2017, 2024 by Scott Ross

I’d ached to see this for so many years and was overjoyed when Olive Films restored and released it. Seeing it, I was not in the slightest bit disappointed and still see this every few months. Now, the martini is drained and there’s no more olive films.

Dismissing this film as a mere “graft” shows that Ebert was mostly just a movie geek; the kind who will interrupt a film to say, “Whip pan! Step-framing! Oil Dissolve!” while watching a film. Such people miss the forest for their need to show-off their perceived expertise in trees (although I plead guilty for the many times I’ve interrupted with “That’s Paul Frees talking!” which reminds me: Why is Max Julien’s distinctive voice dubbed here?)

How’s this for a double feature: Up Tight and The Liberation of L.B. Jones, which you mention.

That LP cover. THAT’S one of the Trauner sets!

Ebert is astonishingly overrated. I suppose one benefit of the know-nothing, short-attention-span crowd taking over eventually is that none of them know who he was. (Of course, they don’t know who Humphrey Bogart was either…)

I feel as you do about the loss of Olive Films. Fortunately, I have since they went belly-up managed to grab copies of their Blu-rays for this one, and a few other movies. Naturally the professional collectors are driving up the prices of whatever titles remain on the market. Nothing good can exist in America without some assholes ruining it.

A double-bill of “Up Tight” and “The Liberation of L.B. Jones” could send me over the edge into suicidal ideation, as watching “Firecreek” and “Welcome to Hard Times” back-to-back also undoubtedly would.

And I have yet to see Welcome To Hard Times, since you described it as “Firecreek without the laughs.”