By Scott Ross

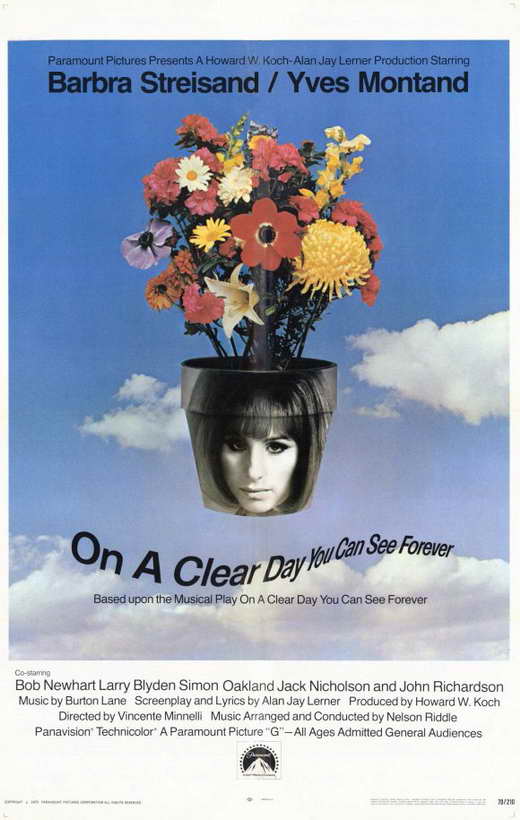

While not a great movie musical, On a Clear Day… has been a personal favorite of mine since I saw it on television in the mid-’70s and it remains an engaging comic fantasy, lushly directed by Vincente Minnelli and beautifully shot by the gifted Harry Stradling Sr.* Its chief progenitor, Alan Jay Lerner, is likewise one of those creative figures, first encountered in childhood, toward whom I admit having very few critical faculties; his lyrics usually seem first-rate to me, and even when I know his book-writing isn’t on a par with them there is always something to enjoy in his work. The original stage musical was troubled (it’s never a good sign when you replace your leading man on the road) but the score was glorious, Lerner’s typically literate and witty lyrics sitting atop Burton Lane’s wonderful melodies like gems in a royal diadem. Although the show was not a great success, such were the times then that even a moderate hit musical could get a movie sale, what with all the studios chasing that ever-elusive “next Sound of Music.” And since Barbra Streisand had recently won the Academy Award for Funny Girl and was filming Hello, Dolly!…

On a Clear Day… was as iffy a proposition for the screen as it had been for the stage, dealing as it did with a mousy little zhlub named Daisy Gamble desperately trying to quit smoking to please her stuffy boyfriend and with psychiatry, hypnotism, ESP and reincarnation thrown into the mix. (After Frederick Loewe retired, Lerner had tried to get it going as the self-punning “I Picked a Daisy” with Richard Rodgers but their partnership never jelled.) On a Clear Day was planned and shot as a three-hour road-show attraction, with more of the show’s charming songs in the can, including a bizarrely costumed futuristic sequence at the end. One can well imagine the panic among the Paramount suits as the costs and the running time rose. Someone had second thoughts, anyway, probably after the box-office failure not only of Dolly! but of Paramount’s previous Lerner road-show Paint Your Wagon, and an hour was summarily cut, mostly musical numbers… the very reason the picture was made to begin with.† Curiously, Minnelli never mentions this in his memoirs, although a few vocal tracks have surfaced, such as Larry Blyden and Streisand performing the slyly satirical “When We’re Sixty-Five” (the deletion explains why Blyden’s role as her controlling nerd of a fiancé feels truncated) and Jack Nicholson’s attractive light baritone number “Who is There Among Us Who Knows?”, new to the score, as was Streisand’s amusing duet with herself (“Go to Sleep”) and her gloriously sexy, nearly pornographic, ballad of seduction “Love with All the Trimmings,” whose orchestral introduction is an instrumental of the show’s mock-madrigal “Tosy and Cosh.” Allegedly Streisand’s “On the S.S. Bernard Cohn” was filmed, and cut; you can still hear a bit of its melody in the underscore of the scene where Yves Montand takes her to dinner. And while the show’s “She Isn’t You,” refashioned from a love ballad sung by the philandering husband of Melinda, Daisy’s earlier incarnation, to a solo for Yves Montand, was likewise trimmed, Streisand got a feminized version, sung to Montand, as “He Isn’t You.” (I told you I love this score.)

Minnelli developed a reputation for caring overmuch about surfaces and less about content — during the filming of Some Came Running he had an entire ferris wheel moved a few feet, twice — and for being old-fashioned in his artistic outlook. (The ’60s were not a great decade for him.) But On a Clear Day has a bright, contemporary look to it that distinguishes it cleanly from his fabled Technicolor MGM musicals like Meet Me in St. Louis, An American in Paris and The Band Wagon, or even the more stylistically relaxed Gigi. The only time his designer’s mania goes wonderfully unchecked is during the Regency “regression” sequences, where Daisy is revealed in her 19th century incarnation as Melinda Tentrees and the lush surroundings (which include the Royal Pavilion at Brighton) and Cecil Beaton costumes suit the narrative. For a man supposed to have been “past it,” Minnelli contributes some amusing contemporary touches, such as the delightful way Montand’s “Come Back to Me” sequence is shot and edited, taking in Central Park, Lincoln Center, some thrilling helicopter shots of the Pan Am building (ask your parents) and, wittily, having the Frenchman’s voice coming out of the mouths of chefs, children, poodles and an elderly couple whose distaff side is represented by the great Judith Lowry. I don’t wish to take anything from Lerner, who adapted the screenplay from his musical book, but this clever notion feels directorial to me. Likewise, while the flashback to Melinda’s orphanage childhood is obviously written, it’s shot in high comic style, like a knowing spoof of Oliver! On the other end of the humor scale are Lerner’s misogyny (“Oh, God! Why didn’t you create woman first, while you were still fresh?”) and his having Montand’s interest in reincarnation spark a trendy little riot by students “seeking a fresh cause for rebellion.”

No wonder so many young people in the Sixties hated musicals.

Speaking of Lerner: He too was at an ebb in the late ’60s, after the twin phenomena of My Fair Lady and Gigi and the succès d’estime of the stage Camelot. Yet even for the movie of Paint Your Wagon, despised by many, he was able to come up, in “A Million Miles Away Behind the Door,” with my very favorite lyric in “There’s so much space between the waiting heart and whispered word.” And if his On A Clear Day wisecracks occasionally fall flat, especially when Montand is required to speak them (“Melinda’s soul inside of you? God! What a housing shortage!”) the lyrics he wrote for the musical contain some of his sharpest metaphors, most cunning japes and best plays on words. Take this, from “Hurry! It’s Lovely Up Here”, sung to the flowers we see growing in time-lapse in Streisand’s rooftop garden:

Wake up, bestir yourself

It’s time that you disinter yourself

and:

RSVP, peonies, pollinate the breeze

Make the queen of bees hot as brandy

and:

Come up and see the hoot we’re giving

Come up and see the grounds for living

Or, in the verse to the title song:

And who would have the sense to change his views

And start to mind his ESPs and Qs?

Or, in “Love with All the Trimmings”:

For I’ll decode every breath and every sigh

‘Til your every lover’s wish is fulfilled before it’s made

Toss in some jealousy and doubt,

Should it be required,

Not rest ’til there’s nothing more desired

Or, in “Come Back to Me”:

In a Rolls or a van,

Wrapped in mink or saran

and:

Let your tub overflow,

If a date waits below, let him wait for Godot!

and:

Come in pain or in joy,

As a girl — as a boy!

Or, in “What Did I Have I Don’t Have Now?”:

I don’t know why they re-designed me

He likes the way he used to find me

and:

I’m just a victim of time, obsolete in my prime

Out-of-date and outclassed by my past

and:

Why is the sequel never the equal?

Why is there no encore?

and:

What would I give

If my old know-how still knew how?

(Lyrics © Chappell & Co., Inc.)

I don’t think Noel Coward or Cole Porter would have been ashamed to have written any of those lines, but there didn’t seem much honor for Lerner in having done so. Well, perhaps it was the times; in the era of Woodstock and Jesus Christ Superstar it was hard to get much of anyone other than Sinatra fans and music saturated show-queens interested in the rarified craft of the Broadway musical. Consideration of which never seemed to bother Burton Lane, whose melodic invention in On a Clear Day is no less felicitous than in the more highly acclaimed Finian’s Rainbow, whose 1968 movie, despite Fred Astaire and Petula Clark, is nowhere near as much fun as this. While generally speaking and except for the “Come Back to Me” sequence New York City isn’t used terribly well, I very much admire Nelson Riddle’s characteristically peppy arrangements of the songs and even small things like the clever main and end titles by Wayne Fitzgerald which mirror the notion of past, present and future lives in a vast, ever-moving continuum.

Montand was and is considered lugubrious as Melinda’s long-distance lover, and he can be a bit heavy-going, but John Cullum, the show’s male lead after Louis Jordan was axed in Boston, was unknown to movie audiences and, aside from Frank Sinatra and in spite of all the big, overblown studio musicals of the period, there weren’t many male singing-and-acting stars around. (Dick Van Dyke, the only popular screen actor/comedian of the time with musical bona fides, would have been all wrong for this.) Larry Blyden, who made something of a career of the type, contributes a perfect Second City portrait of blinkered ambition as Daisy’s boyfriend and Mabel Albertson is warm and motherly as Montand’s secretary, but Simon Oakland’s role as his academic colleague seems as truncated as Bob Newhart’s as a buttoned-down college prexy, the sort of thing he could almost do in his sleep. Jack Nicholson’s part, stripped of its music, I mentioned before, but not Roy Kinnear’s as the Prince Regent, his presence reduced to a single scene and hardly worthy of his rich comic gifts.

And now we come to Streisand… and a small sigh of regret. Although her comic aplomb and timing are intact, and while she looks luminous as Melinda in the Regency sequences, her performance as Daisy is oddly irritating. It’s as if she wanted to make the cleavage between Melinda and Daisy so complete there could be no bleed-through from one to the other, but by doing so she makes Daisy less an endearing oddball than a slovenly, whining frump. It’s a strange performance, one that teeters on the precipice of obnoxiousness and doubtless sent some admirers of the show back to the Original Cast Recording, where they could take solace in Barbara Harris’ infectiously loopy take on Daisy Gamble. Even Streisand’s singing as Daisy is problematic, affected and so overburdened with hand gestures there are times she seems less like herself than some satirically minded drag-queen doing a keen parody of her. (That terrible, teased-up pageboy haircut of hers doesn’t help either.) She’s better when calmer, when expressing comic anger at Montand, or when, as Melinda, she tamps down on the annoying mannerisms. And she looks great in those Beaton costumes, infinitely better than she does in the militantly unflattering Arnold Scaasi schmattes Daisy is forced to wear. She sings better as Melinda too; nothing in her early 19th century incarnation is forced, or overdone, as is nearly everything she does as Daisy. Her characterization reminds me of John Simon‘s great aperçu, in which he asserted that if Streisand were to be hit by a Mack truck “it would be the truck that would die.” Daisy Gamble could land a semi in traction.

As nice as it would be to see the road-show edit of On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, I am not waiting for Paramount to search their vaults for the cut numbers, any more than I expect the company to release the original cut of its Blake Edwards/Julie Andrews flop Darling Lili. (So far, they haven’t even issued a Blu-ray of the previous DVD, merely a repackaged version of that.) Perhaps if the studio was still self-owned, it might care, but as it, and nearly every other major studio, is controlled by a multinational corporation — in this case, Viacom, which purchased it from Gulf + Western — no one who’s been paying attention to these things over the last several decades could reasonably expect a bottom-line organization to spend two cents on legacy.

Say what you will about the vulgar old moguls of the past, but at least they actually loved movies; Viacom, like most entertainment conglomerates, gives a damn only about immediate profit. Even on a clear day, pennywise suits like them can only see the present.

*I also remember seeing the television teaser trailers for the picture in 1970, before I really understood who Streisand was, and their repeated refrain (“This is Barbra Streisand?”) as they depicted her in various costumes and personas.

†Perversely, Paramount, in the persons of Robert Evans and Gulf & Western’s Charles Bludhorn, pushed Blake Edwards to add more and more musical numbers to his Julie Andrews comedy-with-music Darling Lili, and to shoot complex aerial sequences in Ireland during its wettest months, then blamed him for the cost overruns. Lili ultimately fared worse at the box-office than On a Clear Day when it opened a week after Minnelli’s picture, at least partly because it cost three times as much to make. The more modestly-budgeted On a Clear Day had a clearer path to profit, especially with Streisand starring in it.

Text (aside from the excerpts from Lerner’s lyrics) copyright 2021 by Scott Ross

Having myself ‘dipped my tow’ into past life recollection I find this film wonderfully true to the experience, if singing a song afterward is accepted. What is also interesting is that it was conceived and made years before Dr Brian Weiss published his groundbreaking work, “Many Lives Many Masters”. I’m wondering, is there anywhere where one can watch the “3 hour” version of this film?

Thank you for that unique perspective, Hans. Alas, I have been unable to locate anything like the 3-hour cut. It’s probably moldering in some vault behind the Bronson Gates.

It was only the umpteenth time I watched OACDYCSF that I realized Daisy’s orange dress at the finale was the same as Melinda’s brown dress at the orphanage. Same hat too. Thank you Mr. Minnelli!

Now that you point it out, David, it seems obvious. I bow to your eye. Or something.