By Scott Ross

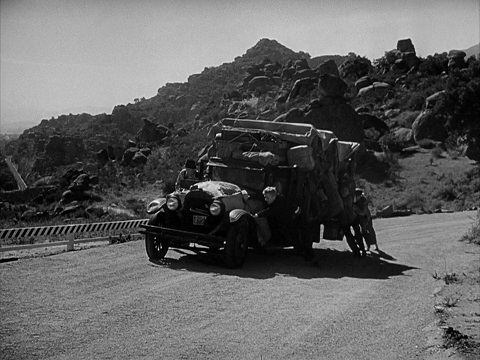

Nunnally Johnson’s very fine adaptation of the epoch-capturing John Steinbeck novel, directed with extraordinary sensitivity by John Ford and photographed by Gregg Toland with almost shocking documentary realism, The Grapes of Wrath is among the least artificial sound pictures of Hollywood’s so-called Golden Age. Although Brian Kellow in his biography of Pauline Kael found retrospective fault with the critic Otis Ferguson for not objecting to what Kellow deems the picture’s “studied and self-conscious artiness,” there is little (aside from the occasional scene shot on a 20th Century-Fox soundstage) that stands between the viewer’s emotions and the movie’s visceral, and deeply humane, emotional punch.

Along with the contemporary photographs of Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans depicting the nation’s rural dispossessed, Steinbeck’s 1939 novel is what many Americans remember when they think of the Great Depression. (Assuming, of course, they know of those things at all now, including the Depression itself, which considering the generalized ignorance of Americans today is not a bet I’d care to take.) The Grapes of Wrath — the title was a suggestion of Steinbeck’s wife’s — addresses both the general and the specific: The former via its author’s digressions between the narrative chapters concerning the causes of the Dustbowl and how it affected the largely sharecropping tenant farming families that had been working the land as they were instructed to, which resulted in stripping the soil of its nutrients* and the latter through Steinbeck’s limning of one of these families, the Joads, as they trek from Oklahoma to California in search of sustaining work, the dream (so the Joads find out, too late) of so many thousands of similarly disaffected and displaced others, and one that quickly turns to ashes in all their mouths.

I’m embarrassed to admit I’ve had a copy of the novel for decades without until very recently getting around to reading it, and I did so only after an aborted run at the Leonard Gardner novel Fat City, which was so unrelentingly grim that although it is fewer than 200 pages long I felt forced to abandon it less than halfway through. You might think that The Grapes of Wrath, if you’ve seen the movie and know how essentially dark the story is, would be equally as relentless as a book about failed boxers in the 1950s, but it isn’t. Although the comedy in the novel is often serious, it’s comedy nonetheless, rich and human and all the more striking and appreciated by the reader because so much of what surrounds it is so unsettling. (Fat City by contrast contained not only no laughter, it held no smiles — even They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? is less depressing.) Of course, some of the humor in Steinbeck’s book is of an… shall we say “earthy”?… variety, and could no more be included in a movie in the 1940s than the extraordinary final image of the novel in which Rose of Sharon Joad, whose feckless husband has left her on the road and who has recently delivered a stillborn baby, offers her mother’s milk to a dying man, one of several passages in the book that raised the predictable ire of the morally censorious across the land and led to charges that The Grapes of Wrath was at best obscene, at worst pornography. Those guardians of the public weal ca. 1939 would blanch and fall into a collective coma could they but behold the literary and pictorial landscape of today. Yet somehow, in spite of them, Ford and Johnson were able to retain the moment when in the government-run camp the Joads’ youngest, Ruthie and Winfield, encounter their first flush toilet. (O horrors!)

My only real complaint about The Grapes of Wrath as a novel is that Steinbeck’s periodic interjections, while informative in themselves, are often intrusive and occasionally unsuccessful exercises in style, large swaths of would-be poems in a book whose depictions of stark Depression-era reality are already un-forced prose poetry. Their sociological and agricultural usefulness aside, the real value of these interstitial chapters if you’re an admirer of the Ford movie lies in seeing how cleverly Nunnally Johnson lifted some of the dialogue in them for his screenplay, smoothly placing the lines into the mouths of the characters in the picture. The agonizing flashback scenes in which Muley Graves (the extraordinary John Qualen) confronts the banker evicting him from his land and the young Caterpillar operator bulldozes his family’s mean little home, for example, come from these chapters; while in the novel they are not associated with Muley per se Johnson seems to have instinctively understood the dramatic power of these passages, and assigned them to the character. Those sequences are among the most striking, and moving, in the picture and Qualen, so often stereotyped in supporting “Swede” roles, is shockingly effective in them. Muley is one of the lost in both the book and the movie — people who either have some sort of breakdown that puts them permanently outside human society or who succumb to the lure of the promised land of California and are destroyed by its brutal reality, such as the beaten-down laborer the Joads meet on their way in who is going back home after losing his entire family to malnutrition, or indeed simply expire from the strain of their eviction as do Grandpa and Grandma, both of whom die on the road when, left alone on the land they cultivated, they might have gone on for years.

There are a couple of odd elisions in the picture and I’m unsure whether they were the result of cutting scenes that were written and shot, or whether Ford (or his boss, Darryl Zanuck) didn’t think we’d notice, but they’re hiccups that can distract you. The first is the inexplicable loss of Noah Joad (Frank Sully). In the novel he decides to abandon the trek and live off the Colorado River; in the movie he just disappears, with no explanation. The second is the speech to Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) by the one-time preacher Casy (John Carradine) in which he outlines his current philosophy and which Tom quotes to Ma (Jane Darwell) when he leaves the family near the end. But since we never hear Carradine speak the lines, we’re a little confused when Tom says, “Well, maybe it’s like Casy says. Fella ain’t got a soul of his own, just a little piece of a big soul. The one big soul that belongs to everybody.” The omission is all the more noticeable because it leads off the movie’s most famous monologue.

Speaking of souls: While the Steinbeck novel is concerned with many, the Ford/Johnson/Zanuck movie concentrates on only a few. Authors of books of course can afford to be more expansive than filmmakers, and the people who put together the movie narrowed it down to a quartet: Muley in the beginning, Casy in the middle and toward the end, and Tom and Ma Joad throughout. And although Johnson’s script otherwise displays remarkable fealty to its source, the narrative arc was altered, presumably to give the audience (and the Joads) a sense of hope denied to readers of Steinbeck’s book. In the novel, while their early experiences in California are discouraging, things improve markedly when the Joads reach the clean, democratically ordered government camp run by a kindly FDR stand-in (Grant Mitchell in the movie); when they leave this sanctuary in search of work, things go from insupportable bad to nearly incomprehensible worse. The Ford picture reverses this to a degree, eliding over the worst of it, although I should add that the Joads are hardly sitting pretty when the movie ends, and the ultimate fate of Tom, who has killed a cop in self-defense, is left entirely in doubt. Ford ended the picture with Fonda going off into the morning mists in extreme long shot but Zanuck, quite rightly I think, found this unsatisfactory. His ending goes back to an observation of Ma Joad’s from the novel (“We’re the people that live”) which, thematically, links up rather nicely with Tom’s “I’ll be all around in the dark” speech.

While I suspect that Steinbeck is truer to life than Zanuck and Johnson (and even Ford) I don’t regard the slightly more upward trajectory of the movie as ruinous, especially when nearly everything else in the picture is so beautifully right, beginning with the casting. Fonda, who knew how important the role of Tom Joad was and how perfectly it fit him, even submitted to a seven-year indentured servant contract with Fox to play it. (Zanuck wanted Tyrone Power, if you can imagine such a thing. I can’t.) The actor, although about a decade older than the character, is still so raw-boned and youthful looking he’s believable enough physically. And Fonda carries Tom’s anger coiled within him so that no matter how outwardly calm he is from scene to scene, you feel — as Ma Joad fears — it may boil over into violence at any moment. But that is only part of Tom, and Fonda gets his essential gentleness and likability, especially in his scenes with his mother. Who, having seen it, can forget the way he croons “Red River Valley” to her as they dance together? Tom’s leave-taking at the end is a masterpiece of restraint; although his speech borders on self-conscious poetics, the way Fonda performs it, with both quiet conviction in his voice and the unspoken ache of parting in his moist eyes, is one of the high-water marks of American screen acting.

Darwell was not Ford’s ideal Ma Joad; he wanted Beulah Bondi, a wonderful actress who might have been just a bit too gaunt. Although the actress is stouter than Steinbeck’s description of that hardy woman, and inclined at times to conventional emotions, when she pushes beyond them she elevates herself, and the picture, into a realm very close to sublimity, as in those final scenes, or when she silently goes through a box of mementos, burning most of them but retaining a pair of dangling earrings. You can spend hours wondering what those baubles were purchased for (a country dance? a church event? her wedding?) and why they mean so much to her, and ruminating on Darwell’s hurt demi-smile as she regards her own reflection. Half of our response to this scene depends on the way Ford depicts it — although he was often as sentimental about mothers as he was about Ireland, his self-control here is exquisite — but surely the other half is due to Darwell.

One of the most remarkable performances in The Grapes of Wrath is, along with Qualen’s, also one of the two least expected, and least commented upon: John Carradine’s as Jim Casy. Carradine, who had one of the great voices in the movies, could be enjoyably hammy — elegantly florid and overstated, especially when playing villains. He (and perhaps Ford?) scaled Casy in realistic terms and his stringbean physique is perfect for the role. Casy’s is the novel’s philosophical voice, and the character who over the course of the book moves furthest, not geographically but in his own mind. When the story begins, Casy not only tells Tom that he’s no longer a preacher but extrapolates at length on his evolving theology, hence the “little piece of a big soul” to which Tom alludes. The character slowly begins to find his place, not as a preacher but within the secular family of man; first by claiming he’s knocked out a murderous cop in a migrant camp when he hasn’t, which allows the man who did so to escape, and later by joining with striking workers, where he meets his death at the hand of a vicious strike-breaker. (It’s that act of murder which causes Tom to inadvertently commit homicide.) Casy is never dogmatic, or doctrinaire, and you can see by the smile on his face when he lets himself be arrested that by taking up for the downtrodden he’s finally found his place in the world. All of that and more is in Carradine’s beautifully judged performance.†

Each of the supporting roles is as well cast as the leads. Charley Grapewin, best remembered as Dorothy’s Uncle Henry in The Wizard of Oz, makes Grandpa moving without a hint of bathos; when he dies on the road to California his last act is to reach out his hand and grasp a piece of earth, as if to re-anchor himself to what has been taken from him. Zeffie Tilbury renders Grandma as comfortable in her somewhat bizarre senility, until she loses the husband she seems to neither be able to live with nor without. Pa Joad is diminished by events he has no control over, and knows it, and Russell Simpson captures this depressed and emasculated sense of loss and confusion with numbed bemusement just as Dorris Bowdon as Rose of Sharon locates the teenage sullenness and hurt of the pregnant young wife callously abandoned by a husband who lacked the fortitude even to tell her goodbye. Although Ruthie and Winfield are not as wild, nor as belligerent toward each other, in the picture as their literary counterparts, Shirley Mills and the very young Darryl Hickman are exceptionally believable without recourse to any sort of movie cuteness, and Hickman has a charming moment when he expresses, with a click of his tongue, his regret at not getting to see any “man bones” in the desert. Eddie Quillan, previously one of the innocent defendants in Ford and Lamar Trotti’s Young Mr. Lincoln, does not telegraph the ultimate defection of Rose of Sharon’s young husband Connie Rivers but lets you see the fear and discontent building in him slowly so that when he leaves the family in the night it isn’t a shock to the viewer but is yet another, seemingly inevitable, loss for Ma, whose family is quickly contracting to a smaller and smaller unit and will probably shrink further when her son Al has had enough. O. Z. Whitehead does a creditable enough job with that role, but he’s many years too old for Al and that fact leeches something vital from the material when, instead of being a randy 16-year-old obsessed with girls and engines he’s a man of almost 30. Frank Darien’s Uncle John barely registers, not because of any deficiency in the actor’s performance but because the movie reduces his character, and his importance. I wish the picture had room for Ivy and Sairy Wilson, the middle-aged couple the Joads pick up and who assist them in many ways, not least of which is burying Grandpa, but Ward Bond has a nice scene as (hold onto your hats) a helpful policeman.

As to that “studied and self-conscious artiness” with which Brian Kellow dismisses Ford’s (and by extension Toland’s) work: If the accusation is true of The Grapes of Wrath it is true of nearly every Ford picture, as well as of City Lights and Citizen Kane and The Night of the Hunter, and any number of movies which have given people pleasure and expanded their horizons over the last 100 years. Of greater note, it seems to me, is Ford’s avoidance of cliché and sentimentality, starting with the spareness of Alfred Newman’s score, which consists solely of renditions of “Red River Valley” during the main and end titles. (It has nothing to do with Oklahoma but everything to do with Tom and Ma Joad.) Even when a scene is precariously balanced on the edge of sentiment, like the one in the diner where Pa goes to try purchasing half a loaf of bread for Grandma, Ford’s restraint is evident, from the way he shoots it to the performances he elicits from the actors. I suppose Kellow may have had in mind items such as the way Muley’s flashlight illuminates the faces of Tom and Casy in the Joads’ abandoned home, or the long tracking sequence, unique for Ford if not for Toland, as the Joads enter the mean migrant camp and the people in it are seen as if through the truck’s windshield. Is that “studied”? Perhaps so. But it brings the terrible poverty at the heart of Steinbeck’s novel into striking relief as the filmmakers dispassionately record the faces of these beaten down men, women, youths and children. These are the living faces, translated from reality to cinematic fiction, that Roosevelt had in mind when he made his speech citing “one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished.” If the depiction of them is “self-conscious artiness,” so be it. We would do well to study these faces. We’ll likely be seeing them in profusion, if not joining them ourselves, ere long.

*It should shock no one who has studied, even cursorily, the extra-Constitutional and essentially illegal Federal Reserve to discover that even one of its former Chairs, Ben Bernanke, admits the Fed did much to cause the Great Depression. Naturally, fingers were instead pointed at small investors for over-speculating, and small farmers for destroying the soil. The same principle is at work today in the Netherlands, where farmers who have for decades been sold the notion that they needed chemical fertilizers are now told, in a blatant attempt at an instant and massive land-grab by the powerful, that they are being promiscuous with nitrates and must stop raising food animals or forfeit their farms. One imagines the increasingly beleaguered (and, one hopes, soon-to-be-dethroned) Speaker of the House cursing herself for not having thought of something similar.

†Although the actor was in 11 Ford pictures the two did not get along. Perhaps because his stepfather, in Carradine’s words, “thought the way to bring up someone else’s boy was to beat him every day just on general principle,” he disliked bullies — and the insecure Ford always had a whipping boy on his movies.

Text copyright 2022 by Scott Ross